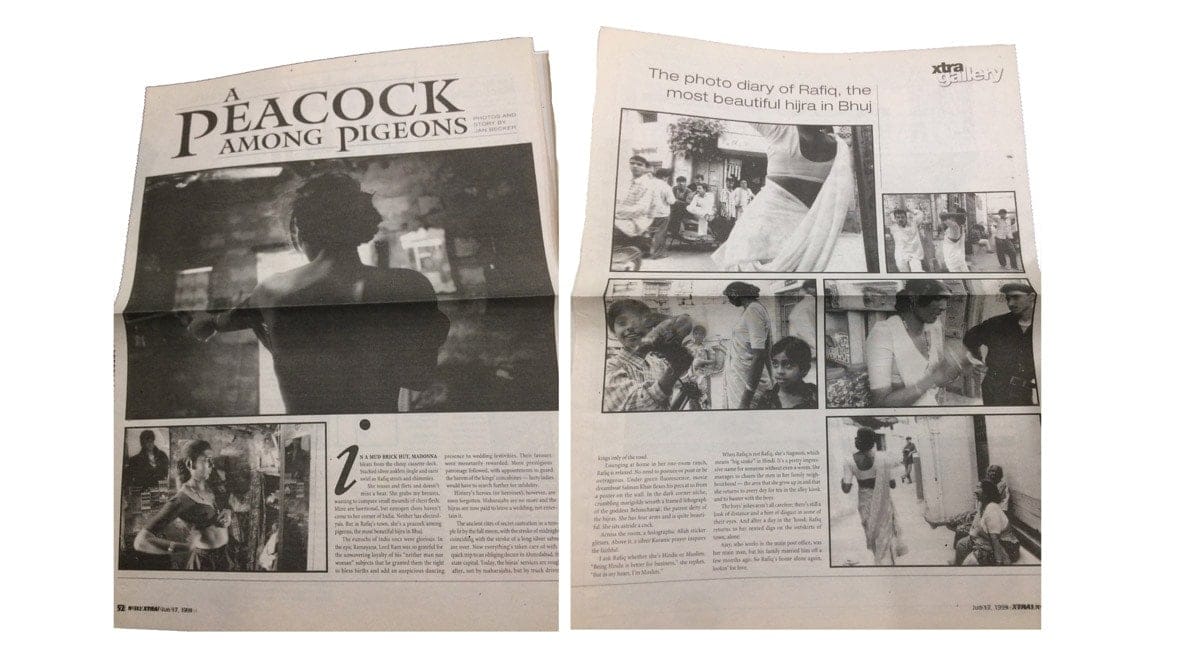

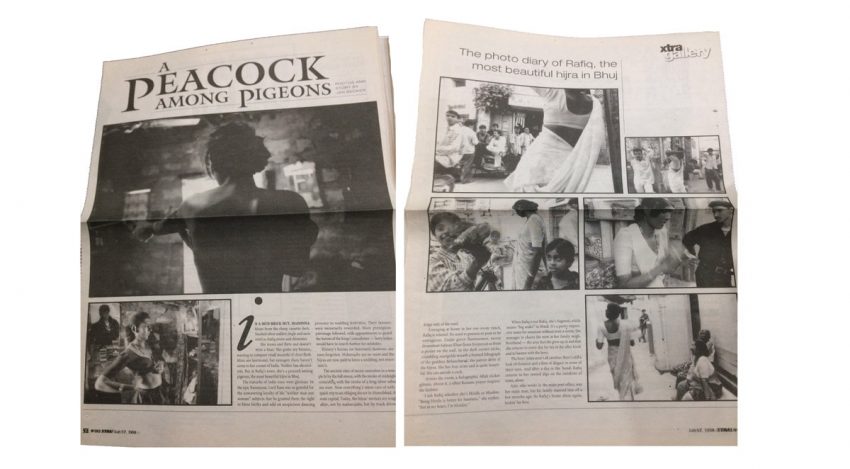

In dis/patches from the Foreign Office, Sajdeep Soomal explores newspaper articles, legal cases, and other ephemera stored in The ArQuives’s international collection.  Issue 3 Becoming Nagmoti Rafiq is exceptional in Jan Becker’s eyes: she is a peacock among pigeons. If you listen to Punjabi bhangra, you should know that the moorni (peacock) is a popular character in the subcontinent. Cropping up in folktales, stories and poems, the peacock has been long appreciated for its colour, gate and eyelike markings on its feathers that promise to ward off the evil eye. In 1963, the peacock was declared the official bird of India because of its ubiquity across the new postcolonial nation. But in the Euro-American imagination, the peacock remains a rare beauty while domestic pigeons – once housed in ornate dovecotes across Europe – have turned into feral pigeons, city pigeons, street pigeons – nuisance birds that signify the dirtiness of a city. Becker inadvertently mobilizes longstanding racist colonial tropes in his catchy title: Rafiq becomes the exotic beauty in a dirty, unclean land overrun by natives. Yet despite her beauty, Becker finds Rafiq’s behaviour innocent and almost childlike if not weird, it is another instance of the failed modernity of the third world. Becker – who is transitioning herself – also points out that estrogen shots have not yet arrived in the India economy. In many ways, we can sense how the persistence of colonial capitalism impedes the possibility for global trans solidarity, for an equal field to transition into the future. Taking a closer look at the text, we learn that Rafiq has another name: Nagmoti. Becker explains that in Hindi, Nagmoti means “big snake.” I wonder what Nagmoti would think of being called a moorni. In 1999, there was no place for hijras in the secular nation. Like the snake, hijras belonged to the underworld of 1990s Indian society. As the hijra rights movement gains tractions across the subcontinent, it is possible to imagine Nagmoti becoming the national moorni of India. But knowing that Nagmoti was publicly Hindu because “it was better for business” in her hometown outside of Ahmedabad, I think the worst. Witnessing the parallel rise of Hindu fundamentalism over the past twenty years in Gujarat and across India, I wonder if Nagmoti made it through the 2002 Gujarat pogrom. I wonder if she still listens to Madonna. I wonder if the holographic Qur’anic sticker in her room still glitters.

Issue 3 Becoming Nagmoti Rafiq is exceptional in Jan Becker’s eyes: she is a peacock among pigeons. If you listen to Punjabi bhangra, you should know that the moorni (peacock) is a popular character in the subcontinent. Cropping up in folktales, stories and poems, the peacock has been long appreciated for its colour, gate and eyelike markings on its feathers that promise to ward off the evil eye. In 1963, the peacock was declared the official bird of India because of its ubiquity across the new postcolonial nation. But in the Euro-American imagination, the peacock remains a rare beauty while domestic pigeons – once housed in ornate dovecotes across Europe – have turned into feral pigeons, city pigeons, street pigeons – nuisance birds that signify the dirtiness of a city. Becker inadvertently mobilizes longstanding racist colonial tropes in his catchy title: Rafiq becomes the exotic beauty in a dirty, unclean land overrun by natives. Yet despite her beauty, Becker finds Rafiq’s behaviour innocent and almost childlike if not weird, it is another instance of the failed modernity of the third world. Becker – who is transitioning herself – also points out that estrogen shots have not yet arrived in the India economy. In many ways, we can sense how the persistence of colonial capitalism impedes the possibility for global trans solidarity, for an equal field to transition into the future. Taking a closer look at the text, we learn that Rafiq has another name: Nagmoti. Becker explains that in Hindi, Nagmoti means “big snake.” I wonder what Nagmoti would think of being called a moorni. In 1999, there was no place for hijras in the secular nation. Like the snake, hijras belonged to the underworld of 1990s Indian society. As the hijra rights movement gains tractions across the subcontinent, it is possible to imagine Nagmoti becoming the national moorni of India. But knowing that Nagmoti was publicly Hindu because “it was better for business” in her hometown outside of Ahmedabad, I think the worst. Witnessing the parallel rise of Hindu fundamentalism over the past twenty years in Gujarat and across India, I wonder if Nagmoti made it through the 2002 Gujarat pogrom. I wonder if she still listens to Madonna. I wonder if the holographic Qur’anic sticker in her room still glitters.