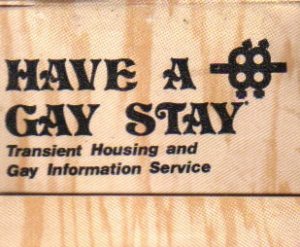

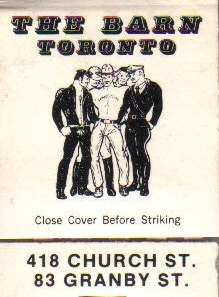

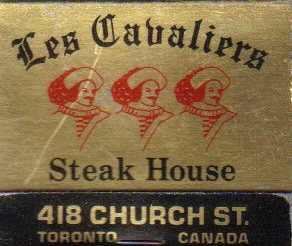

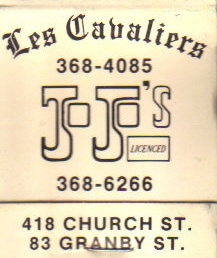

In 2015, it can be hard to remember the days when you could actually smoke in bars at all. For many of us, it’s probably been years since the last time we’ve even really thought about the fact that in those days, bars and restaurants printed and distributed their own branded matchbooks to give out to customers who smoked. And, of course, gay and lesbian bars and restaurants were no exception. The ArQuives maintains a collection of matchbook covers, which open a window into the history of the LGBT communities. The names and addresses of bars and restaurants and bathhouses, often long since closed, where our tribes gathered to meet and socialize and drink and have sex and fall into or out of love; organizations which helped to build the community we know today; changing trends in marketing and graphic design. These are just a few of the many stories that this collection can tell. The Barn remained one of Toronto’s best-known gay clubs into the 1990s and 2000s, but several of the matchbooks trace a history not as well-remembered: the bar first opened in 1975 as Les Cavaliers, a steakhouse restaurant, and Jo-Jo’s, an upstairs dance club. Unlike the established venues on Yonge Street, it was one of the first gay bars to open further east on Church Street. By the 1980s, it had adopted the more familiar Barns/Stables name, which it held until closing permanently in 2012; today, it’s the location of the Marquis of Granby pub.

In 2015, it can be hard to remember the days when you could actually smoke in bars at all. For many of us, it’s probably been years since the last time we’ve even really thought about the fact that in those days, bars and restaurants printed and distributed their own branded matchbooks to give out to customers who smoked. And, of course, gay and lesbian bars and restaurants were no exception. The ArQuives maintains a collection of matchbook covers, which open a window into the history of the LGBT communities. The names and addresses of bars and restaurants and bathhouses, often long since closed, where our tribes gathered to meet and socialize and drink and have sex and fall into or out of love; organizations which helped to build the community we know today; changing trends in marketing and graphic design. These are just a few of the many stories that this collection can tell. The Barn remained one of Toronto’s best-known gay clubs into the 1990s and 2000s, but several of the matchbooks trace a history not as well-remembered: the bar first opened in 1975 as Les Cavaliers, a steakhouse restaurant, and Jo-Jo’s, an upstairs dance club. Unlike the established venues on Yonge Street, it was one of the first gay bars to open further east on Church Street. By the 1980s, it had adopted the more familiar Barns/Stables name, which it held until closing permanently in 2012; today, it’s the location of the Marquis of Granby pub.

The Twin Peaks Tavern in San Francisco, still open today, has an important place in LGBT community history. Already part of the burgeoning Castro District, it was purchased by Mary Ellen Cunha and Peggy Forster in 1971 – and the following year, it became the first gay bar in the United States to install transparent windows, enabling the patrons to see out onto the street and pedestrians on the sidewalk to see inside. In 1972, when it was still incredibly risky to be seen in the wrong place by the wrong person, most bars were designed to protect their patrons’ privacy and being able to see through the windows was a revolutionary act of visibility. Because police officers still regularly targeted gay and lesbian bars for “morals” violations, Cunha and Forster instituted a “no touching” rule to minimize police scrutiny, and the bar became known as a casual social venue rather than a cruising bar. To this day, it has a reputation as the “Gay Cheers”: a spot where everybody knows your name.

The Twin Peaks Tavern in San Francisco, still open today, has an important place in LGBT community history. Already part of the burgeoning Castro District, it was purchased by Mary Ellen Cunha and Peggy Forster in 1971 – and the following year, it became the first gay bar in the United States to install transparent windows, enabling the patrons to see out onto the street and pedestrians on the sidewalk to see inside. In 1972, when it was still incredibly risky to be seen in the wrong place by the wrong person, most bars were designed to protect their patrons’ privacy and being able to see through the windows was a revolutionary act of visibility. Because police officers still regularly targeted gay and lesbian bars for “morals” violations, Cunha and Forster instituted a “no touching” rule to minimize police scrutiny, and the bar became known as a casual social venue rather than a cruising bar. To this day, it has a reputation as the “Gay Cheers”: a spot where everybody knows your name.

Many more stories, many more glimpses of our changing history, can be found in The ArQuives’s collection of matchbook covers.  Some things, however, never change. Written By: Craig Schiller It can be hard to remember the days when you could actually smoke in bars at all…

Some things, however, never change. Written By: Craig Schiller It can be hard to remember the days when you could actually smoke in bars at all…