Operation Soap: Toronto’s Bathhouse Raids According to The Body Politic

Operation Soap

The front page of The Body Politic’s March 1981 issue reads: “Feb 5, TORONTO: 150 COPS SMASH UP THE BATHS – 286 GAY MEN BUSTED”1. In coordinated attacks, four Toronto bath houses were raided by the Toronto Police over the course of three hours. The bath houses raided were the Richmond Street Health Emporium, The Club, The Romans II Health and Recreation Spa, and The Barracks2. The police arrested 286 people and charged them as ‘found-ins’ in a ‘common bawdy house’3. This was the largest mass arrest in Canada since the Fall of 1970 when Pierre Elliott Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act4 during the October Crisis in Quebec.

The police insulted, beat, and taunted these men, spewing such vitriol as “too bad these showers weren’t hooked up to gas.”5. Police also destroyed the bath houses themselves, smashing glass, doors, and equipment with crowbars and sledgehammers6. One year later, The Body Politic would reveal that “this was not random police malevolence, but part of an organized crackdown, code-named Operation Soap”7. As of March 1982, The Body Politic estimated that the raids cost taxpayers up to 5 million dollars8. These were not the first bath raids in Toronto, or in Canada and unfortunately, not the last, but they were the largest and most destructive.

The Legal Loophole

With Operation Soap, the police used the ‘common bawdy house’ charge as an excuse to persecute queer people. A common bawdy house refers to anywhere “resorted to for the purposes of prostitution or the practice of acts of indecency”9. While queer sex was not illegal, people could be charged for being found in or running a location where such “indecent acts” took place. “As the police see it, gay and lesbian sex may not be illegal in itself, but the places where we do it — even our own bedrooms — can legally be a common bawdy house. We can thus be charged as criminals — as ‘keepers’ and ‘found-ins’”10. During the Operation Soap raids a total of 306 people were charged, 286 patrons were as ‘found-ins,’ while 20 managers and owners were charged as ‘keepers’11. This is why we still must be alert for laws that can be manipulated to criminalize the LGBTQ2+ community.

Privacy Invasions

While the three Toronto daily papers pledged to keep the names of found-ins a secret12, there were significant privacy concerns. The Toronto Police now had the names of all the people arrested, which could be used to target them later. There were also allegations that the police had tampered with individuals’ mail as part of their Operation Soap investigations13.

In an invasion of bodily autonomy, those charged as ‘keepers’ were required to get Venereal Disease tests, and those charged as ‘found-ins’ were given notices recommending VD testing14. This was an invasion of the ‘keepers’ autonomy and also put ‘found-ins’ at risk of being outed if someone saw the notice. There were so many complaints about this that the Toronto Public Health Department removed the policy that ordered VD testing for people charged with sexual offences15.

The Body Politic and The Right to Privacy Committee encouraged those charged to reach out to them, assuring them “that all information given will be held in the strictest confidence”16. However, as the 1977 police raid of The Body Politic offices proved, they could not guarantee the protection of people’s information. Data protection still remains a concern for any organization seeking to help marginalized people in dangerous situations.

Gays Fight Back

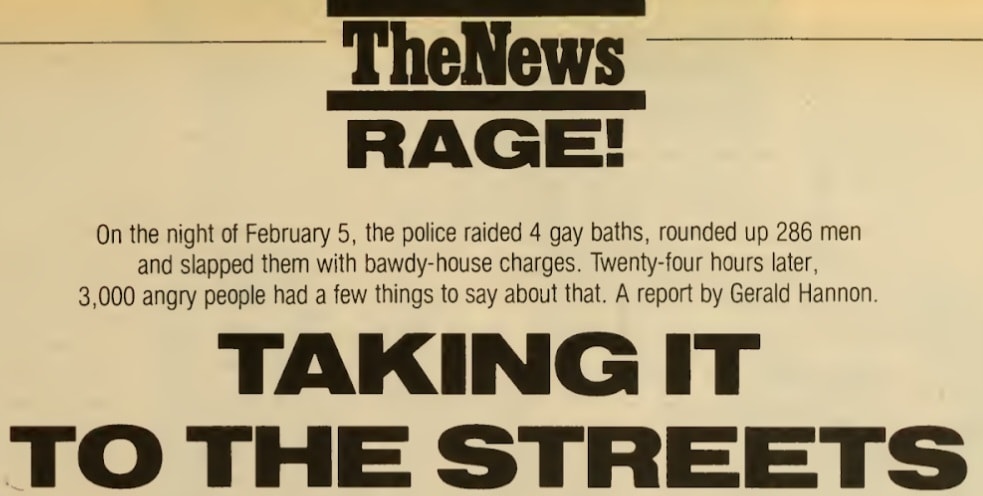

“On the night of February 5, the police raided 4 gay baths, rounded up 286 men and slapped them with bawdy-house charges. Twenty-four hours later, 3000 angry people had a few things to say about that”17. The LGBTQ2+ community and straight allies alike were enraged by the excessive violence the police used during the bathhouse raids. 3000 people marched on the Toronto Police 52 Division and then on Queen’s Park18. As the March 1981 issue of The Body Politic asserts, the LGBTQ2+ community would not apologize for blocking traffic, damaging property, or disturbing the peace in an effort to stand up for themselves:

“Yes, Toronto saw its most militant protest of the last decade. And no, we don’t intend to apologize. We have our own message. It is time for the bigots in Toronto — in uniform and otherwise — to understand that gay men and lesbians will fight back every way we know how. They can no longer expect to harass and intimidate us with impunity. They can no longer attack us and escape unscathed. We will fight back, but we won’t be alone.”19

Police Accountability (or lack thereof)

Ontario’s Attorney General Roy McMurtry refused to hold anyone accountable for the violence of Operation Soap. McMurtry claimed insufficient reports of abuse to warrant an independent investigation20. Alan Borovoy activist and general counsel for the Canadian Civil Liberties Association told The Body Politic, “[i]t is easy to understand why no one would complain when the only body they have to complain to is the police themselves.”21

There were photos proving that cops removed badges and flash numbers during the February 6th protest, making themselves unidentifiable, but Deputy Chief Marks refuted these claims22. There were also undercover cops at the demonstrations, which a civil rights lawyer argued has a chilling effect on the right to freedom of assembly23. This kind of surveillance undermines people’s ability to organize against state violence.

It Worked

These protests and the subsequent work of activist groups were largely effective. During Operation Soap and two smaller raids that occurred later that year, 304 people were charged as ‘found-ins’; only one person was given a criminal record and 36 received absolute or conditional discharges24. This was a success rate of 87 percent. Many attributed this success to the work of The Right to Privacy Committee who encouraged plaintiffs to plead not guilty. “Of those who pleaded not guilty in Toronto, 94 percent were acquitted”25. This demonstrates the power of community organizing.

Operation Soap and the following protests strengthened the community and galvanized the Gay Liberation Movement in Canada. We must learn from the past, be grateful for the work of our queer and trans predecessors, and unapologetically fight for LGBTQ2+ rights.

References

1. The Body Politic. (1981, March). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives.

https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic71toro

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. The Body Politic. (1982, March). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives.

https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic81toro

8. Ibid.

9. The Body Politic. (1981, March). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives.

https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic71toro

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. The Body Politic. (1981, April). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives.

https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic72toro

15. The Body Politic. (1982, March). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives.

https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic81toro

16. The Body Politic. (1981, March). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives.

https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic71toro

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. The Body Politic. (1981, April). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives.

https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic72toro

24. The Body Politic. (1983, April). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives.

https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic92toro

25. Ibid.

Author Bio: Sophie Argyle is a Master’s student in York University’s Communication and Culture program. In her research, she examines the possibilities and limitations offered to LGBTQ+ people by digital media. She is currently writing her thesis about queer people who discovered a facet of their LGBTQ+ identity on TikTok. As an intern at the ArQuives, Sophie is excited to help out the communications team and research historical events that involved the collection of queer people’s personal data.