Hey, it’s Henry! This past summer, I had the immense pleasure and privilege of working at The ArQuives as a research intern. I came to this opportunity through the Maharam Fellowship offered by my school—the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). My goal through this fellowship was to see the collections at The ArQuives through architecture, home, and domesticity. I’ve spent the past few months reading through endless archival materials, conducting numerous site visits, interviewing notable individuals, and working through my findings with the staff at The ArQuives. This has resulted in a book project that I’ve written, designed, and filled with digitized archival material and site renderings.

What I came to realize was that queer people are some of the most inventive users of the built environment. Facing the hate and violence of a prejudiced world, queer architecture is a story of life between the cracks and fissures of society. Public places and parks turned into cruising spots, the steps in front of a coffee shop became a community hub, and bars and bathhouses became spaces of intimacy and gathering.

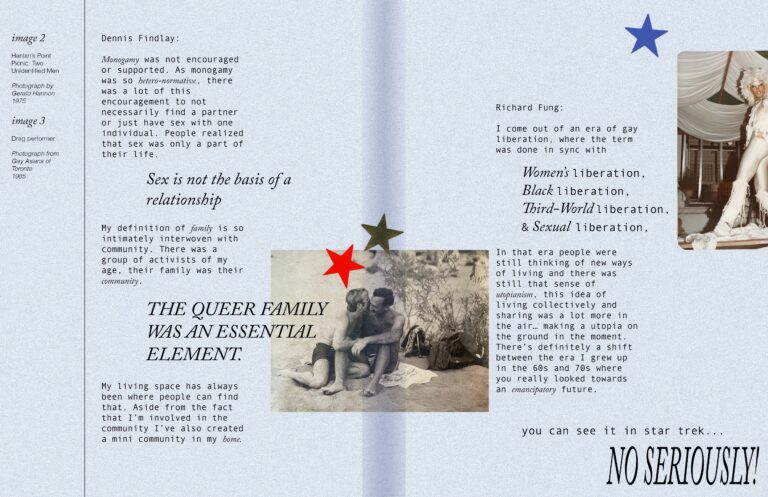

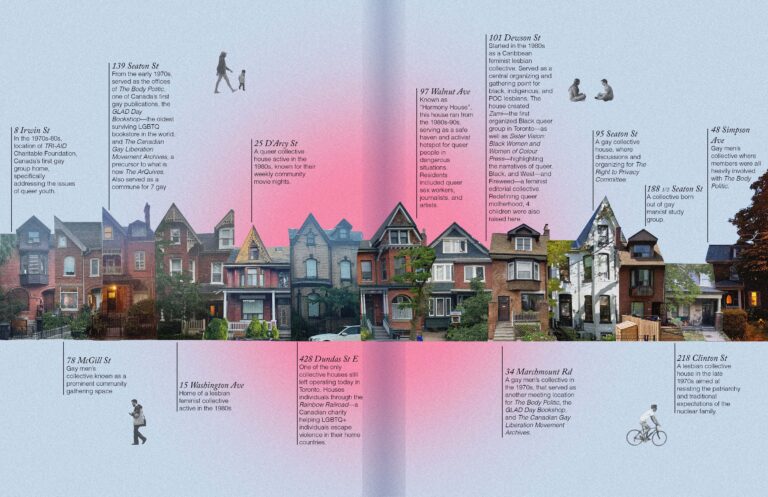

Another one of the most unexpected things I learned this summer was the groundbreaking, almost utopian manner, in which queer Torontonian’s approached domesticity and family. Monogamy, the nuclear family, a single-family home—nothing was sacred, and anything could be reevaluated. Communal houses have become my new obsession. Groups of queer people living together in a site of mutual support? Houses being used by networks of people planning protests, activist organizations, and even blowout parties? Domestic life was flipped, and queer people inhabited space incredibly unconventionally, where ownership, privacy, and labour were divorced from societal standards. Absolutely fascinating.

However, even queer spaces were not always for all queer people. Certain bars and clubs were exclusionary towards women and POC men, organizations were homogenously white, and even the queer culture of sex and domesticity excluded POC from feeling desired or seen. People of colour had to navigate the spaces between their cultural and found families and oftentimes crafted their own spaces independent from the mainstream. These are the stories of those I often sought to include, but still struggle with uncovering.

My time at The ArQuives is tinged with the sadness, joy, and love of the stories I’ve researched. Countless individuals for whom living was an act of resistance in itself—where space could be a sanctuary, a fight, and a utopian vision. My perspective on home, and what I bring with me to my architectural practice in the future, is forever changed. To my intensely passionate, kind, and knowledgeable colleagues at The ArQuives—I am deeply grateful.