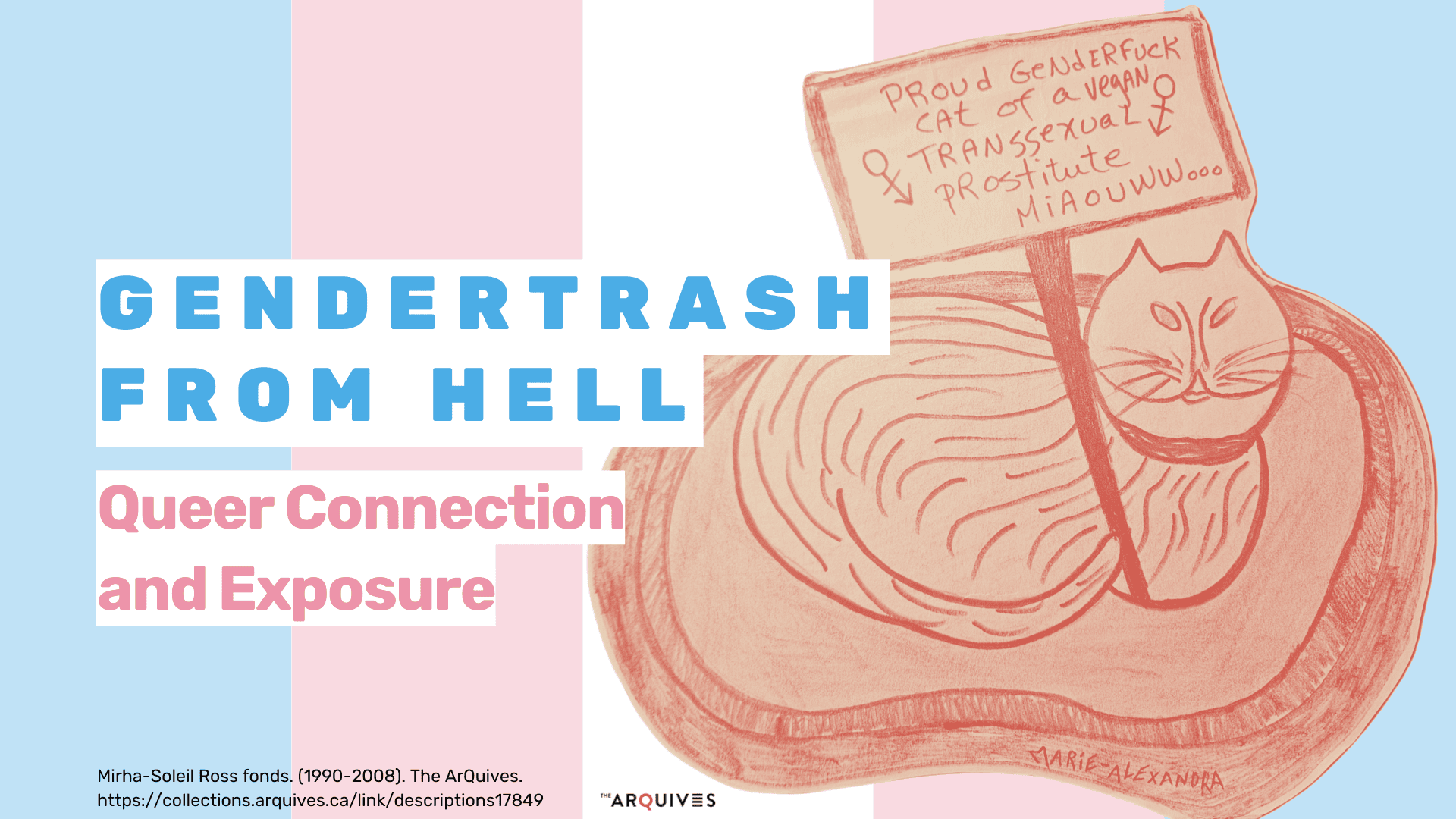

In the early 1990s Mirha-Soleil Ross and Xanthra Phillippa MacKay formed a publishing company called genderpress. Between 1993 and 1995 they produced four zines entitled Gendertrash from hell. The first issue of Gendertrash includes a mission statement: “Gendertrash is devoted to the issues & concerns of transsexuals. Gendertrash also welcomes input from gender positive genetics. in addition to issues of gender hate & oppression, gendertrash is equally opposed to any other forms of systematic oppression by those who are in positions of power.” The zines are an assemblage of articles, poetry, interviews, and visual art curated by Ross and MacKay. Original paste-ups and promotional materials for Gendertrash are also held in the archive, and they help to demonstrate the zine’s intended audience. Sophie looks at Gendertrash collection through the lenses of the intersectionality, community, privacy and risk.

The Zine

Gendertrash from Hell is a zine that ran from 1993 until 1995. It was produced by Mirha-Soleil Ross and Xanthra Phillippa MacKay. The duo ran a small press called Gender Press and produced four issues of the zine. Gendertrash was described as “the Canadian community and politically-oriented publication that addresses the issues affecting the lives of transsexual and transgendered persons”1. Check out our digital gendertrash exhibit to learn more! The four issues of the zine included art, poetry, medical advice, fictional stories, historical biographies and letters from readers. The zine also featured ways to connect with the community such as personal ads, lists of other relevant publications and newsletters, and a “Canadian Directory of organizations, resources and services”. As the issues progressed, they included more advertisements; there were ads for electrolysis services, custom lingerie stores, and creative design services. Gendertrash was circulated across the U.S. and Canada, available in stores from Toronto to Boston to Vancouver to San Francisco2.

The Audience

Interestingly, Gendertrash was not written solely for members of the trans community. It “welcomed input from gender positive genetics”, with genetics refering to cisgender people3. A handbill advertising the zine reads that as well as being for “members of gender communities”, Gendertrash was for “someone who is in social/health services and deals with transsexual/transgender people” and “anyone who wants to know more”4. This shows that the creators saw the zine as a way to educate the general public. Their specific interest in educating service providers who worked with trans people was a clever way to improve trans people’s everyday lives. MacKay and Ross understood that entirely insular or queer-targeted solutions were insufficient. Of course, there was and is value in activism and education efforts within the community, but reaching those outside of the community is crucial for making big and small changes.

Despite Gendertrash being for everyone, Ross and MacKay refused to pander to prudish cisgender readers. The zine’s third issue features a review from Belinda Doree, who wrote “Gendertrash is a hand-grenade disguised as a magazine…there is little concern here for the sensibilities of the prim and proper”5. This zine was provocative in the sense that it was unabashedly erotic, but also in the sense that it was confrontational, daring cis readers to recognize their own transphobia. They had a “Hooker of the Year” article in which Justine Piaget was honoured and interviewed6. Their second issue featured a Genetic Jerk Quiz for cis readers7. Above the quiz, it said, “Take this simple & easy test to see how much of a genetic jerk you really are”. This hilarious quiz received praise in letters to the magazine from people who gave it to their cis friends to take8. By unapologetically highlighting trans sexuality, supporting trans sex workers, and insulting cis people, Gendertrash was intentionally unpalatable and refused to engage in respectability politics.

Intersectionality

Gendertrash took a very intersectional approach to trans issues, discussing how racialized trans people, Indigenous trans people, low-income trans people, trans sex workers, and trans prisoners face different and intersecting obstacles and concerns. Their first two issues read, “[I]n addition to issues of gender hate and oppression, gendertrash is equally opposed to any other forms of systemic oppression by those who are in positions of power”9. Their intersectional approach was intentional and explicit.

Ross and MacKay were sex workers themselves and they advocated for trans sex workers in their zine. In Gendertrash’s second issue, Jeanne B. wrote, “It is time for the larger transsexual community, to start looking at certain [transsexual] prostitutes as role models. We make up a very large and important part of transsexuals as a group. We are strong, courageous, intelligent, self-motivated, insightful and clear-sighted individuals whose stories and lives should not be silenced in order to gain mainstream acceptance”10. Throughout their issues, they followed the story of a missing and murdered trans sex worker, Grayce Elizabeth Baxter11. They also published notices warning other trans sex workers about dangerous potential clients12.

An article about trans experiences of racism and poverty is found in the fourth issue of Gendertrash13. Issue four also included an interview with a two-spirit individual, Dancing To Eagle Spirit, discussing how they experience their gender identity as part of their Indigeneity14. In an article defending against a claim that we still hear today, that “[a] man wanting to be a woman is like a white person wanting to be Black”, Marisa Swangha, a Black cis woman, writes how this argument erases the existence of Black trans people15. Notably, Ross and MacKay were not just discussing these issues, but platforming people with knowledge and experience.

The zine also recognized the differences in the experiences of trans women and trans men. After their first couple of issues, MacKay and Ross were aware of the lack of resources for trans men, and they made a concerted effort to include them in Gendertrash. The first all-FTM (female-to-male) conference was advertised in issue four16. They also sold pins and promoted publications specifically for trans men, such as Boy’s Own and Boys Will Be Boys. Rather than treating trans people as a monolith, Gendertrash made room for different people’s experiences.

Gendertrash was highly popular in prisons. The zine’s creators championed the rights of trans prisoners. In issue four, they shared the realities of trans prisoners, including the voices of the trans prisoners themselves17. This is yet another example of Gendertrash refusing to exclude people who may have made their cause seem unpalatable. With their attention to intersectional oppression, even that which did not affect them personally, MacKay and Ross set an example for any queer people fighting for queer rights.

Terminology

The four issues of Gendertrash were published in a two-year span. In this short time, the terminology used by the zine’s creators evolved. In issue one, readers were described as “[m]embers of the gender communities” and the zine was described as “devoted to the issues and concerns of transsexuals”18. This is interesting, since in the 1990s, the term gender community was often an umbrella term that included non-trans crossdressers19. In issue two, the zine claimed to “[give] a voice to gender described people”20. The term gender described was used to refer to those we would now call transgender, while genetic described referred to those we would now call cisgender. Finally, issue four referred to itself as giving “a voice to transsexual/transgendered people”21. This distinction is interesting since in the past there have been tensions between those who medically transitioned, who called themselves transexual, and those who only socially transitioned, who were called transgender22. Of course, today we understand transgender as an umbrella term for all people whose gender does not align with their assigned sex at birth.

These linguistic changes demonstrate the importance of terminology. These terms can be used to exclude or include people and to give power to the community that identifies with them. Issue one asserts this importance, critiquing the use of terms such as “tranny” or “drag queen” and providing a “[l]ist of transexual words and phrases”23. This issue argued that it was “[t]ime to develop our own language and impose it on this gender suppressive society”24. Terminology is powerful and Gendertrash attempted to form a shared understanding of word meanings that was not available prior to this medium and would become even more possible with the rise of the World Wide Web.

Community Connection

A 1993 article in XTRA! praised the way in which Gendertrash connected the trans community: “In Gendertrash From Hell, they are creating an unprecedented forum for gender activists to come together and strategize – a place they can finally call home”25. This zine offered respite during a time when “[trans] activists [were] in a position [that was] fragile, diffuse, with limited support”26.

There were many letters from readers, asking questions, engaging in discussion, and thanking the creators. One reader wrote, “I’m not sure if I can find the words to properly express the gratitude within me. To actually be able to read, to hold in my hands a magazine that speaks what is in my heart and mind, it is a feeling of joy and empowerment beyond my wildest dreams and prayers”27. Another reader wrote, “I must say how much the initial two issues’ generous soupçons of irreverent wit & self-righteous anger served to help empower my thinking not only towards myself but to fellow travellers as well”28. These letters show how meaningful this zine was to members of the trans community.

The zine pointed readers to other forms of community connection, such as in-person support groups and online forums. For example, they directed readers to access the Transequal bulletin board system on the internet29. This provided an option for readers who are unable to attend in-person meetings due to disability or privacy concerns. Meanwhile, in-person groups were a great option for those who did not yet have access to a computer or lacked technical knowledge. Gendertrash’s focus on creating a community beyond the zine made them a valuable resource.

Gendertrash was also a powerful information hub. Specifically, they offered readers information about gender-related medical procedures. This was significant because, before Google, accessing this information was very difficult. Issue one ran an article about getting safe electrolysis30. Issue two offered information about getting gender-affirming surgery, at the time called a sex-change operation, from someone who had first-hand experience31. This allowed trans people who lacked information, or real-life trans friends, to benefit from the wisdom of their trans siblings and navigate a highly discriminatory medical system.

Beyond providing social support, Gendertrash also offered a space for political strategizing. In its pages, trans people were able to discuss pressing issues that were affecting them, such as media representation, unemployment, women’s shelters, social stigma and violence32. Issue two featured a critique of the exclusion of trans people from the Ontario Human Rights Code; this left trans people unprotected and at risk of being evicted with no recourse33. The zine also discussed the effects that the AIDS epidemic was having on trans people, specifically34. They also shared about acts of protest in which members of the community were engaging35. Gendertrash brought these causes into people’s everyday lives by selling pins that allowed people to express themselves as queer and make political statements.

In a time before widespread internet access, these kinds of publications were invaluable. This zine was a way to connect people “who [had] been discouraged from speaking 36. The creators of Gendertrash brought serious debates and factual information to the people who needed it, all with an air of wit and humour that made the zine feel warm and commiserative.

Privacy and Risk

The value that Gendertrash offered to the trans community was and is undeniable, but I want to acknowledge the privacy risks associated with subscribing to a publication like this one. Since this zine was accessed by mail order, readers had to give their name and address to subscribe. This caused a twofold privacy issue. First, Gender Press kept mailing lists that were detailed lists of people who were in, or involved with the trans community. If police were to seize the list, as they did with the mailing lists of The Body Politic magazine during the 1977 raid, readers would be at risk of being targeted by police surveillance and violence. Second, this zine was mailed to people’s homes. If someone could be outed to spouses, family or roommates if Gendertrash arrived in the mail for them; this could result in abuse or homelessness. Dame-Griff explains that during the era of trans zines, “[e]vidence of past or current membership in a gender community-related group […] risked outing via association”37. Due to these concerns, trans readers had to weigh whether the access to information and support was worth the risk. In the queer community, the trade-off between privacy and community has always been a tension. This is even the case for in-person support groups. One cannot access queer community without exposing themselves to risk in some way. This is a tension that I’m sure most queer people today can understand, and this knowledge should inform how we go about supporting one another and building queer community.

References

1. Mirha-Soleil Ross fonds. (1990-2008). The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions17849

2. Gendertrash From Hell 3. (1995, Winter). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/769

3. Gendertrash From Hell 1. (1993, April/May). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/items/show/764

4. Mirha-Soleil Ross fonds. (1990-2008). The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions17849

5. Gendertrash From Hell 3. (1995, Winter). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/769

6. Gendertrash From Hell 2. (1993, Fall). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/767

7. Gendertrash From Hell 2. (1993, Fall). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/767

8. Gendertrash From Hell 3. (1995, Winter). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/769

9. Gendertrash From Hell 1. (1993, April/May). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/items/show/764; Gendertrash From Hell 2. (1993, Fall). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/767

10. Gendertrash From Hell 2. (1993, Fall). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/767

11. Gendertrash From Hell 2. (1993, Fall). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/767; Gendertrash From Hell 3. (1995, Winter). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/769

12. Gendertrash From Hell 2. (1993, Fall). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/767

13. Gendertrash From Hell 4. (1995, Spring). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/771

14. Ibid.

15. Gendertrash From Hell 3. (1995, Winter). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/769

16. Gendertrash From Hell 4. (1995, Spring). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/771

17. Ibid.

18. Gendertrash From Hell 1. (1993, April/May). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/items/show/764

19. Dame-Griff, A. (2023). The Two Revolutions: A History of the Transgender Internet. NYU Press.

20. Gendertrash From Hell 2. (1993, Fall). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/767

21. Gendertrash From Hell 4. (1995, Spring). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/771

22. Dame-Griff, A. (2023). The Two Revolutions: A History of the Transgender Internet. NYU Press.

23. Gendertrash From Hell 1. (1993, April/May). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/items/show/764

24. Ibid.

25. XTRA! (1993, 25 June). Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights in Ontario fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions29796

26. Ibid.

27. Gendertrash From Hell 3. (1995, Winter). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/769

28. Gendertrash From Hell 4. (1995, Spring). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/771

29. Gendertrash From Hell 3. (1995, Winter). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/769

30. Gendertrash From Hell 1. (1993, April/May). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/items/show/764

31. Gendertrash From Hell 2. (1993, Fall). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/767

32. Gendertrash From Hell 3. (1995, Winter). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/769; Gendertrash From Hell 4. (1995, Spring). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/771; XTRA! (1993, 25 June). Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights in Ontario fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions29796

33. Gendertrash From Hell 2. (1993, Fall). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/767

34. Gendertrash From Hell 1. (1993, April/May). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/items/show/764; Gendertrash From Hell 2. (1993, Fall). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/767

35. Gendertrash From Hell 3. (1995, Winter). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/769

36. Gendertrash From Hell 4. (1995, Spring). Gendertrash: Transsexual Zine, 1993-1995. The ArQuives. https://digitalexhibitions.arquives.ca/exhibits/show/gendertrash/item/771

37. Dame-Griff, A. (2023). The Two Revolutions: A History of the Transgender Internet. NYU Press.

Author Bio: Sophie Argyle is a Master’s student in York University’s Communication and Culture program. In her research, she examines the possibilities and limitations offered to LGBTQ+ people by digital media. She is currently writing her thesis about queer people who discovered a facet of their LGBTQ+ identity on TikTok. As an intern at the ArQuives, Sophie is excited to help out the communications team and research historical events that involved the collection of queer people’s personal data.