Trigger warning: mention of rape and sexual assault.

By Jeff Baillargeon

“Our field investigation has determined that you are a homosexual. How do you respond to this charge?”

This is what members of the federal public service who were suspected of being gay heard once they were seated in a small room—often a storage closet, or a shack in a location unbeknownst to the accused—with three chairs, a small table, a hanging lightbulb, two men and later, a ‘stress’ machine which was supposed to be able to identify homosexuals, or what the campaign called “sex deviants.”

The Fruit Machine, a one hour and 21 minute documentary by Sarah Fodey, tells the story of this machine and the LGBT purge in a series of interviews with historians, lawyers, and select individuals who were targeted and dismissed from their positions by the National Security campaign in Canada for being, or simply suspected of being, gay throughout the 1950s and 60s. In total, approximately 9,000 individuals were purged from the RCMP, Armed Forces, External Affairs, and other federal departments.

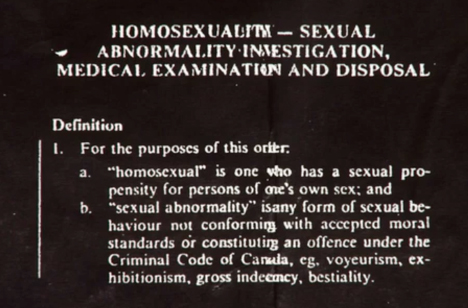

As the historian Gary Kinsman argues, though the Canadian military had been excluding homosexual men since the 1920s, when a policy by the name CFAO 19-20 had deemed homosexuals an “abnormality,” it was only after the Gouzenko Affair that sexuality became a matter of national security. Igor Gouzenko was a Soviet cipher clerk at the Soviet Union’s embassy in Ottawa during the Second World War. Weeks after the war, he defected and provided the Canadian government documents that proved that Russia had established a network of espionage in Canada since the opening of the embassy in 1942. The papers also proved that, throughout the war, they had established networks of espionage in other allied countries. An investigation resulted in the arrest of 39 people and the conviction of 18.

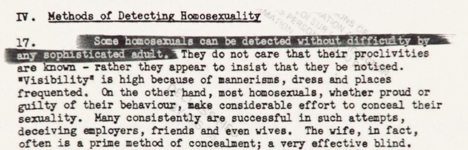

Prior to this crisis, there were no security clearings for federal public servants. After the crisis, as John Sawatski argues, author of the first book on the purge, Men in the Shadows: The RCMP Security Service, public service was never the same. Characterized as a sickness, a character weakness, the men behind the National Security campaign to purge all homosexuals from federal public service argued that LGBT people were not trustworthy, and therefore, a threat to Soviet blackmail and a national security. Sexuality, like race and socialist politics during the Cold War, was identified as an abnormality from the norm of white heterosexual middle class citizenship. This distortion from the norm was seen, by the military, as dangerous to the integrity of the nation. Though ‘character weakness’ also included alcoholism, ‘illegitimate’ children, and promiscuity, 90% of the campaign’s focus was on homosexuals. All who were dismissed, or forced to resign, as a result of the purge, were told not to apply for any jobs requiring a security clearing as they would fail on the basis of their sexuality. It is within this context that Kinsman argues that sexual regulation in the Cold War era was a key component of the war itself.

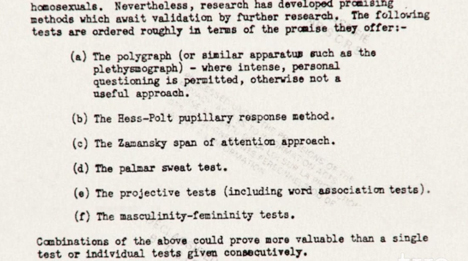

Created by Dr. Robert Wake of the psychology department at Carleton University, this machine was called the Fruit Machine. Commissioned by the RCMP and Canadian Armed Forces, Wake was sent to America to learn about the research being done to identify homosexuals there, and to develop a similar technology here. It is there that he came across a grocery marketing project by a psychology professor where participants’ reactions to particular packaging for food items were evaluated by looking at their pupils and how they dilated. This was called the pupillary response test. Wake determined that a similar test could be created for his mandate, but instead of following participants as they perused market aisles for groceries, individuals suspected of being gay would be repeatedly—over several weeks—seated in a room with a small projector screen where they would be asked to look at sexually suggestive pictures of members of their sex.

But, as internal reports demonstrate, the machine’s reliability remained a problem for Wake and the officials in charge of administering these tests. Pupils dilate for many reasons unrelated to arousal such as lighting, changes in the objects displayed before them, stress, fatigue, and so on. For the better part of a decade, the government invested tens of thousands of dollars in the Fruit Machine project until it was finally disbanded at the end of the 1960s. This did not mean, however, that the purge ended. Canadian civil rights lawyer and counsel for the class-action lawsuit against the government for the purge, R. Douglas Elliot argues that when the Liberal government of Pierre Elliot Trudeau decriminalized homosexuality (albeit, only in the private sphere of the bedroom) the purge did not end, but actually intensified. The rationale, he argues, was that the campaign only had a few more years left to get rid of all the queer people in the military, foreign affairs and national security services because, as public opinion would change, the purge would become intolerable to the nation.

“We were interrogated like war prisoners,” an interviewee relates, “we were thrown in the back of a car, driven to an undisclosed area and interrogated for hours and hours.”

“Every week they were hauling me into that shack. Always asking sexually-oriented questions,” another says.

After repeated and failed attempts at getting a confession from the accused, “they start screaming, ‘Ok, you’re suspected of being a lesbian. We want names of all your friends, and we want them now, and you’re not going to get out of here until you talk!”

When individuals resisted, or refused to resign, they were threatened with being outed: “If you don’t resign, we’re outing you and then firing you.”

In what Kinsman calls a “climate of violence” surrounding LGBT people at this time, many individuals left the federal public service without being able to tell their friends and family why they had resigned or been dismissed. This left people with immense pain, a shame that some say they still carry with them today. As one woman relates, “I felt so dirty […] You don’t want to see your family or friends. You don’t want to talk about it. So, you do drugs.” Many were left homeless, abandoned by their families, when outed by the campaign, and many turned to drugs, alcohol, and suicide.

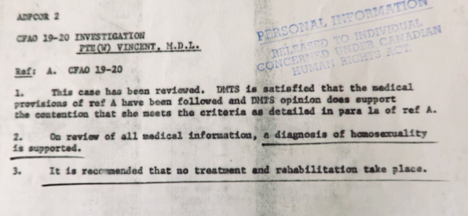

For many, however, leaving the military was not as simple as being dismissed, told to pack up their things and to ‘get out.’ First, they were asked if they would consider rehabilitation. But this request was merely a formality for many, who upon refusing conversion therapy, were taken to psychiatric hospitals for weeks, or months at a time, until a doctor eventually declared them a ‘lost cause.’ Fighting tears relating her story, one woman explains that upon having a breakdown when she realized that “[i]t was over,” she made the mistake of trusting a nurse who came to take care of her. She later found herself at St-Joseph’s Hospital in the psychiatry wing, where she was kept against her will for two months—heavily medicated—until they allowed a family member to come pick her up.

The campaign, however, was not a secret operation within the RCMP, nor the Armed forces. Once a member of the military was suspected of being gay, they were subject to harassment, sexual assault, and in some cases, rape. “There was this backlash. I don’t know how else to put it,” one woman says. “One night,” she continues, trying to hold back tears, “I was raped by three soldiers, because, I was told, I didn’t know what having a big one was. To this day I still do not know who these guys are because they blindfolded me.”

The campaign to purge homosexuals from the federal public service left an indelible mark on this generation of queer people in Canada. Stalked and photographed in public for weeks and months at a time, routinely taken away for hour-long interviews, forced to take lie-detector tests alongside the fruit machine, harassed and/or sexually assaulted on the base, gay federal public servants came to live in a constant state of paranoia.

It was not until the year 1990 that this practice ended, when Michelle Douglas, a former Operations Officer with the Special Investigative Unit—dismissed during the purge—launched a lawsuit against the military; and it was not until the year 2017 that the federal government officially recognized and apologized for the purge in the House of Commons, after having settled a $110 million class-action lawsuit for victims.

But for many, as expressed in the documentary, though welcome, the apology will not heal the pain that was inflicted on them. As one woman presciently stated: “This whole thing broke part of our soul. I think it broke the person that we were supposed to be, to where we were supposed to go. I think it broke part of us. It will always be broken. […] We were good people. […] And we would have helped so much. […] And I noticed talking to people discharged like me that they were the best. That we were the best. That I was part of the best. And it shouldn’t have happened.”

To conclude I end with a statement by R. Douglas Elliot, the lawyer for the class action lawsuit:

“I believe most Canadians are fair people. But they need to understand that it actually happened. That our country, not the United States, not the United Kingdom, not ISIS, or some other horrible entity. The Government of Canada, and the RCMP, and the Canadian Armed Forces pursued this policy of targeting gays and lesbians, and investigating them, and interrogating them, and branding them as people suffering from a character weakness and a threat to national security and threw them out onto the street after they had volunteered to help our country. It was a disgraceful episode in our history.”

http://thefruitmachine.ca

https://www.tvo.org/video/documentaries/the-fruit-machine-feature-version http://lgbtpurge.com/about-lgbt-purge/ https://rabble.ca/toolkit/rabblepedia/fruit-machine https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/the-fruit-machine https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/igor-sergeievich-gouzenko