Written by: Craig Jennex There has been a great deal of interest in Jim Egan’s early activism since the release of Historica Canada’s new Heritage Minute. The short film, entitled “Jim Egan,” is the first in the series that takes up LGBTQ2+ issues. You can watch the Heritage Minute here. The ArQuives (The ArQuives) is proud to hold and care for Jim’s collection—journals, correspondence, photographs, tabloid clippings, notes, ephemera, and much more. This brief post provides more information about Jim’s life and activism in the 1950s, as well as a few previously-unreleased photographs.

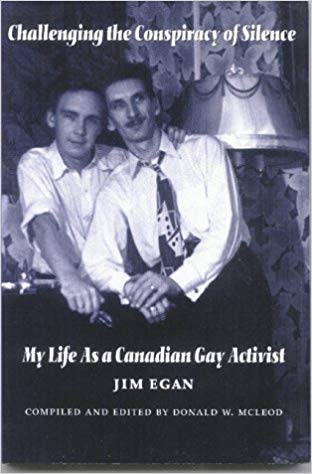

Challenging the Conspiracy of Silence

—

After a brief stint in the Merchant Navy, Jim returned to Toronto in 1947. He met his partner Jack Nesbitt in early August 1948 at the Savarin Hotel—a space frequented by gay men formerly located at 336-44 Bay Street. Later that month, Jim writes in Challenging the Conspiracy of Silence, he and Jack “exchanged rings and agreed to commit themselves to each other” (119).

“Jack and Jim in 1948.”

—

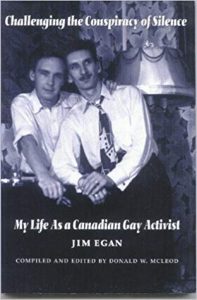

After World War II, disparaging media representations of homosexuality (particularly representations of men who had sex with men) increased. There are a number of reasons for this. In his book Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War Two, Allan Bérubé argues that WWII sparked a massive coming-out process in the United States. The war, he writes, removed millions of young men and women out of their familial homes and small communities and placed them in sex-specific spaces and situations. For young people whose sexual identities were forming during these years, this caused a severe disruption to the authoritative hold of heterosexuality. While homosexual acts existed throughout history, it’s post-WWII that homosexuality as an identity marker really takes hold. Additionally, some popular novels from the 1940s and 50s included homosexual desires, experiences, and themes, including Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar (1948) and James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room (1956), bringing attention to homosexuality to a mainstream audience. And, as one final example, Alfred Kinsey’s Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male was published in 1948. Two of the claims Kinsey made in this text shook North American readers and received wide coverage in the press: first, he argued that there were far more men who had participated in (or desired) same-sex erotic experience that one might imagine and, second, you can’t always tell a homosexual male simply by looking at him. These are just a few developments that altered public perceptions of same-sex desire and experience. In short: as homosexual possibilities became more widely-known—and as homosexuality became more closely aligned with an identity rather than an act—pushback against homosexuality increased. Accordingly, mid-century Toronto was a dangerous place for men to act on their desires for other men. There were few spaces to meet and socialize and, because of the increasing media attention to the so-called threat of homosexuality, police in the city regularly cracked-down on the few spaces in which men would meet. In Challenging the Conspiracy of Silence, Jim writes that police would often use handsome police recruits in their early twenties as bait in an attempt to catch gay men. These recruits, he notes, “would sprawl out on a park bench, and call out a friendly ‘Hi, how are you tonight’, to any man who passed…the young man might then stretch out and rub his crotch and say, ‘Oh man, am I ever feeling horny tonight’. Well, that’s all it took. As soon as the gay man laid a hand on him, bang, he was arrested and charged with committing an act of gross indecency…In some cases the cadet was feeling horny and allowed the gay man to give him a blow job, only to arrest him later” (42). The penalty for such a crime was usually about one hundred dollars. The real danger, though, as Jim notes in his book, “was having your name, age, and sometimes even occupation and address printed in the local scandal sheets, which were always interested in publishing news of local ‘sex crimes’” (42). In the 1950s, media representations of men who have sex with men were absolutely brutal. Toronto tabloids like True News Times, Justice Weekly, and Hush published sensationalized takes on the “sex deviants” and “perverts” who were “infecting” the city. (Similar tabloids circulated in Quebec—Montréal Confidential, Can-Can, Tabou, Ici Montréal, among others—during this period. Will Straw, James McGill Professor of Urban Media Studies at McGill University, has compiled examples of a number of “Québécois journaux jaunes” on his website here.) Here are some examples of how gay men and lesbians were described on the front pages of Toronto tabloids:

“Representations of gay men in Toronto tabloids.”

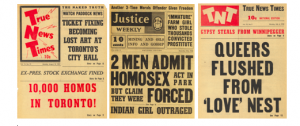

“Homosexual Concepts” by J.L.E.

“Egan’s corrections.”

“Egan’s correspondence.”

—

It’s clear, looking through this correspondence, that Jim’s letters were vital for so many people in the moment they were published. Jim’s writing sparked a collective re-assessment of what homosexuality meant in the 1950s. His letters altered the way homosexuals were represented and provided a more positive perspective on homosexuality that provided the necessary framework for a number of activists and groups in subsequent decades. His activist work in the 1950s is foundational for LGBTQ2+ organizing in Canada.

—

For more information on Egan’s early activism, see Don McLeod’s entry on Egan in The Canadian Encyclopedia available here and/or this detailed CTV segment.

—

Craig Jennex is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Faculty of Media, Art, and Performance at the University of Regina and a sessional instructor at McMaster University. He is currently writing a book on LGBTQ2+ history in Canada that will be published by The ArQuives in 2020.