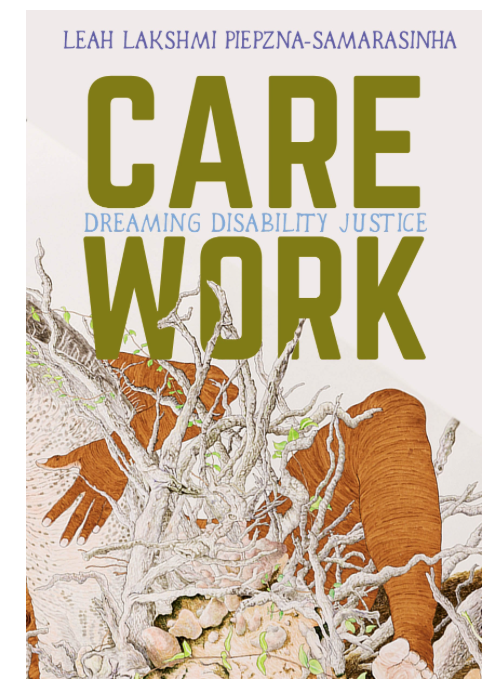

Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice, by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s

By: Lo Humeniuk

Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice is a compilation of essays that the artist/ author/ activist has written over the course of the last eight or so years.An inspiring record and call to action, this book has just been nominated for the Judy Grahn award for Lesbian Nonfiction from The Publishing Triangle.

Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha published her first book in 2006 and has had several published since, but her work as an artist and activist reaches much further back than that. Care Work functions in in a bevy of ways, simultaneously as a memoir of how Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha has navigating activist spaces—and space in general—since the 1990s while also functioning as a helpful toolkit and rallying cry for the world to step up and reframe how we look at, consider, and perceive what the author refers to as sick and/or disabled bodies and minds. It must be noted that there are many terms within our vernacular for those with disabilities- Lydia X. Z. Brown has written a piece on the use of ‘disabled’ versus ‘differently abled‘ which is well worth a read, and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha has discussed her choice of using the word ‘crip’ in an interview with Eleanor J. Bader—and for the remainder of this piece, I’ll be using the terminology that Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha uses in her text.

What is disability justice? While the term encompasses a broad range of concepts, it essentially looks at the intersections between communities “where disability is not defined in white terms, or male terms, or straight terms” and which centres queer, trans, Black and brown people. The movement, initiated by a group called Sins Invalid, stipulates in its mandate that progress is to be made concurrently at a pace “with no body left behind.” Sarah Jama, co-founder of the Disability Justice Network of Ontario, stated at the Hart House Hancock lecture earlier this month that disability justice is about the right to exist.

Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha states fairly early on in the book that she is “not an academically trained disability scholar” and this works as a strength—the book maintains accessible language as opposed to resorting to elitist jargon to convey the ideas she wants to express. Despite her claim, she has been trained—through lived experience. She describes collectives and projects that she has been part of, in addition to drawing upon historical movements such as the Rolling Quads, who rallied for independent living centres, STAR House, a safe house for trans people of colour, and Sins Invalid, a performance collective, and she uses these examples to show the actuality of collective effort. She pays homage to those who have done the work before and alongside her, such as Mia Mingus, Joan Nestle, Stacey Milbern, E.T. Russian, and Patty Berne. In addition to mapping a historic progression of disability justice thus far, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha also provides a resource guide of articles, books, documents, lists of questions for critical self-reflection, and websites to explore. She weaves these throughout her essays, sharing links to documents that provides fragrance-free organizing toolkits, for example, as well as a list of “Questions to Ask Yourself as You Start a Care Web or Collective, and Keep Asking.”

Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha challenges the general public’s view of the sick and disabled, and calls for a reframing. What if access wasn’t a service begrudgingly offered, but instead acted as “a collective joy and offering we can give to each other?” What if, she asks, care webs were designed to function on the premise of “solidarity, not charity?” The recognition of the mutual benefit of care work, and of the importance of a collective, community-based approach, is imperative. Mutual aid and a collective approach can help remove pity and superiority from a participant’s mindset regarding care, and helps fill a void caused by inadequate funding and support. Beyond this, she explores barriers to access, and the complexities of care: “I think about the many people I know and love who have a really hard time receiving care because ‘care’ has always been conditional, or violent—the invasion of social workers or Child Protective Services or psychiatrists with the power to lock you up.” We need to reframe care work as an ongoing collective action instead of a chore. As the author simply puts it, we need to “Normalize access and disability[…] Realize you are or will be us.” The notion of a venue scrambling to figure out a solution to an accessibility issue should not exist. We simply need to put measures in place to accommodate all bodies in the first place.The author further emphasizes that we all “are or will be” disabled through the example of what happens when an able-bodied person gets hurt or needs help. This “temporary spring into action,” she notes, reflects ableist attitudes within society in that it highlights how unaware most able-bodied people are to those with needs different from their own. Often in these situations, she adds, care webs fade out because “it isn’t the fun ‘cause of the moment’ anymore.” Effective care webs must be sustainable, and the author points out that able-bodied people have a lot to learn on this matter.

The author has achieved several things with this book. On the one hand, she has done just what she has quoted Mia Mingus (another disability justice advocate), as saying; “we must leave evidence.” Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha states “I want disabled QTBIPOC to find each other, find our work, our paradigms, our tools, our stance, our hacks and art and love […] There is no disability justice archive yet.” In this book, she has created a record of sorts, to start off that archive. On top of this, she celebrates survival skills and the skill sets and knowledge unique to sick and disabled queer, trans, Black and brown people but, she argues, “I want EVERYONE to have crip knowledge.” This book, and its resources and signposts are a great starting point. This book somehow manages to be a critique of ableist attitudes while simultaneously ushering those who are able-bodied into the fight.

Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha brings many questions to the fore in her essays, such as: What is considered activism? How is activism practiced within disabled communities? What is disability justice? A question that lies at the root of this book, however, is “What do you think healing is? Do you think that it means becoming as close to able-bodied as possible?” This challenge—that we reconfigure and really examine what is both meant by and what the purpose of ‘healing’ actually is—declares healing as a nuanced, individualized, ongoing process. Her critical analysis on how able-bodied people frame the world and frame sick and disabled QTBIPOC is encapsulated herein and reveals the root of disability justice itself. We need to stop viewing some bodies and minds as less than, as broken.

While the author’s statement is correct—there is no disability justice archive yet—the ArQuives has several books on the subject to inspire you to dig further. We have other works by Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha including Consensual Genocide and Dirty River: A Queer Femme of Color Dreaming Her Way Home, as well as a collection in which she is featured titled Marvellous Grounds: Queer of Colour Histories of Toronto. In addition, we have QDA: A Queer Disability Anthology, edited by Raymond Luczak; Pushing the Limits: Disabled Dykes Produce Culture, and Women, Sexuality & Disability: Peeling Off the Labels, both of which are edited by Shelley Tremain; and Queering Urban Justice: Queer of Colour Formations in Toronto, which features a piece co-written by Nwadiogo Ejiogu & Syrus Marcus Ware.