By Alisha Stranges and Elio Colavito

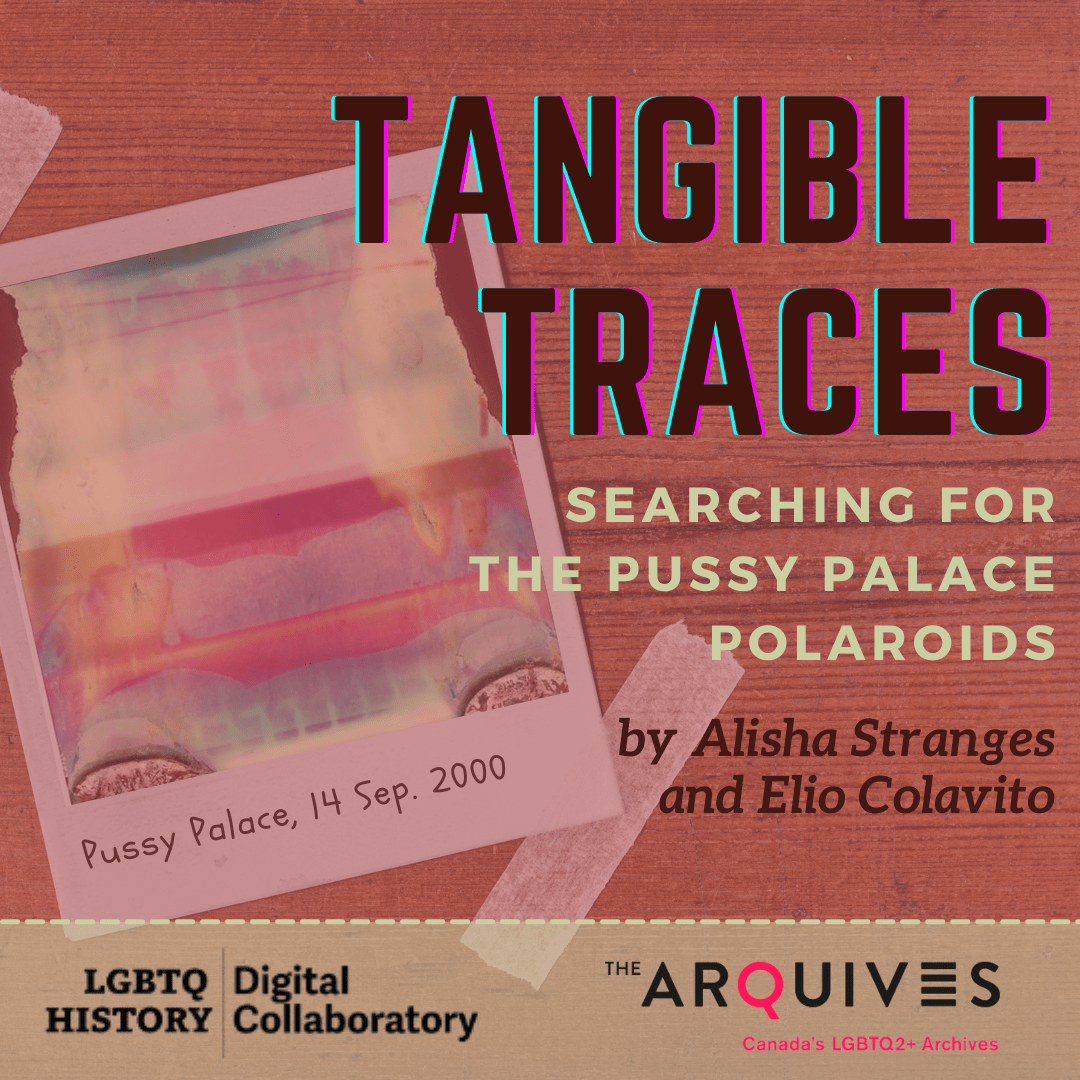

Did you know that the 2000 Pussy Palace had an instant photo room? On the fourth floor of the Palace, a sign reading “porn/photo room” directed patrons in two equally playful directions: towards a room for screening pornography and/or towards a room for having Polaroids taken to document one’s night at the bathhouse (Blair 163; Vogels paras. 10-13). In our most recent oral history interview, Carlyle Jansen, one of the founding members of the Toronto Women’s Bathhouse Committee, shared that the use of instant photography was an entirely conscious decision on the part of the event organizers. Beyond offering patrons a fun thing to do, Polaroids afforded a certain degree of privacy that allowed patrons to document scenes of unbounded erotic exploration, free from risk or regret. In Jansen’s words:

You took [the Polaroid] with you. Nobody else had a copy of it. You could keep it. And it was your choice if you gave it to somebody else, but at least there was a limit.

In other words, you could take a daring or salacious photograph of yourself, alone or with others, without fear of it being reproduced and circulated without your consent.

Hoping to recover a Polaroid or two for the historical record (with consent of course), we’ve been asking narrators if they recall spending any time in the photo room on the night of the raid. Quite surprisingly, there are a few surviving snapshots. How wild would it be to gaze upon one of these images or, even better, to grasp one between your fingers?

Polaroid (or “instant”) photography is a particularly fascinating type of archival evidence because a Polaroid is entirely of the moment and singular. Visual Studies scholar Peter Buse outlines the three basic properties that distinguish instant film technology from all other forms of photography: 1) the near immediate appearance of a physical print; 2) the elimination of the darkroom, which removes human intervention from the development process; and 3) the singularity of the image — since a Polaroid’s negative and positive are fused, the image cannot be reproduced (37).

These three unique properties make Polaroid technology the optimal choice for documenting one’s night at the bathhouse. The prints are ready in seconds, and the scenes and subjects they capture can remain private. Add to this that each image is one of a kind and you can see how the Pussy Palace photo room offered patrons hassle-free access to a personalized souvenir of a night to remember.

But, what is perhaps most captivating about the possibility of uncovering the Pussy Palace Polaroids is the tactile connection they provide us to the space and time of the raid. As curator and author Nat Trotman argues, the Polaroid disrupts conventional understandings of photography’s relationship to memory, time and place, subject and object — particularly when used in a “party” situation (10). Trotman writes:

Over the course of a minute, a photograph does not concern remembering or forgetting. Rather, it plays between the lived moment and its reification as an object with its own physical presence. The party Polaroid is not so much an evocation of a past event as it is an instant fossilization of the present. It solidifies the constant slippage of present into past and remains after the party as a real physical manifestation of the party itself. It relates to the party not by means of its decay but of its production, revolving less around death than life. (10; emphasis added)

Thus, the brilliance of Polaroid technology lies in the intimacy it offers between the subject of the photo and the photo as an object unto itself. Unlike standard photography — or, even, digital photography — there is very little distance between the act of taking a Polaroid and the act of observing it. Since a Polaroid camera can print a physical image seconds after deploying the shutter, Polaroids are both records and remnants of the event. They not only commemorate the event but also participate in the event as it occurs. As Jean Baudrillard puts it, “the Polaroid photo is a sort of ecstatic membrane that has come away from the real object” (quoted in Buse 44). To hold a Polaroid in your hand, then, allows you (in some sense) to touch the space and time in which it was captured, gaining an otherwise unattainable proximity to what transpired.

The Pussy Palace photo room did not simply produce private souvenirs of the night; it produced tangible traces of the night that make the 2000 Pussy Palace impossibly immanent. Let’s hope there remains a wealth of these image-objects waiting to be rediscovered in the junk drawers of our narrators.

—

Works Cited

Blair, Jennifer. “‘What We Do Well’: Writing the Pussy Palace into a Queer Collective Memory.” torquere: Journal of the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Studies Association, vol. 6, 2004, pp. 143-67.

Buse, Peter. “Photography Degree Zero: Cultural History of the Polaroid Image.” New Formations, vol. 62, no. 1, 2007, pp. 29-44.

Jansen, Carlyle. Interview by Alisha Stranges and Elio Colavito for the LGBTQ Oral History Digital Collaboratory, April 1, 2021, Zoom video recording, The ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives, Toronto ON.

Trotman, Nat. “The Life of the Party.” Afterimage, vol. 29, no. 6, 2002, p. 10.

Vogels, Josey. “Polite Gal Love.” NOW Magazine, 21 Sep. 2000, https://nowtoronto.com/news/polite-gal-love. Accessed 30 Mar. 2021.