By James Gunn

The ArQuive’s National Portrait Collection honours individuals who have made significant contributions to diverse out and proud lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans communities in Canada. One its latest inductees, David Rayside, teaches at the University of Toronto, where he helped to create their Sexual Diversity Studies Programme (now the Mark S. Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies), the Committee on Homophobia and the Rainbow Triangle Alumni Association. He was an active member of the Right to Privacy Committee (RTPC) and a collective member of The Body Politic, one of Canada’s first significant gay publications. I interviewed Scott Rayter who nominated David to be recognized as part of the collection.

Scott teaches in the Department of English and at the Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies at the University of Toronto. In addition to courses on American literature, he teaches classes in sexuality/LGBTQ studies, HIV/AIDS, and contemporary queer art, literature and film in Canada. About 10 years ago, Scott co-curated (with longtime ArQuives volunteer Don McLeod and Maureen FitzGerald of SDS) and wrote the catalogue essay for Queer CanLit, a joint venture with The ArQuives and the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library. He is currently working on the second edition (with Laine Zisman Newman) of Queerly Canadian: An Introductory Reader to Sexuality Studies in Canada to be published next year.

Tell us more about Queer CanLit and David Rayside’s contribution.

When the first edition of Queer CanLit was put together in 2012 the goal was threefold: to create a text that could be used in LGBTQ2+ studies courses; to bring together some of the outstanding and important scholarship being done in this country; and to offer a different perspective and narrative to a field in which mostly American scholarship is taken as representative or universal. The book serves as a great reminder that Canadian history is far from boring when it comes to sexuality. David has a piece in there about why, in Canadian Schools, we have seen slow progress and uneven implementation of policy and practice around the recognition of sexual and gender diversity, especially compared to a number of places in the US, despite what many of us would assume and that goes against the kind of story we like to tell (about) ourselves in relation to our neighbor to the south.

How did your professional relationship with David develop over time?

I first met David when I started my PhD at UofT and attended a meeting in 1997 for the relaunch of the Positive Space campaign, which David had spearheaded a couple of years earlier—a program so successful it’s been copied on campuses all across North America and beyond. I was struck by how effective a leader and consensus builder David was, and I could see the deep respect he had for others, especially students, and what they had to say. In so much of the work he has done at UofT at the Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies—and beyond, with initiatives such as the RTCP (created in the wake of the Bathhouse Raids), or The Body Politic, and EGALE—you can see David’s commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion, and a real understanding of the sometimes difficult and transformative institutional and structural change that’s required to make that happen. I admired from the get-go his ability to work with anyone, to take on the powers that be and even get adversaries on board, and how effectively he handles crises and facilitates solutions. David has also been a generous and supportive mentor over the years to so many of us—including to so many students—when starting out and taking up leadership roles ourselves. I started out as a teaching assistant in 1998, and went on to become the Associate Director running the undergraduate program for nearly 10 years, and I learned so much from working closely with David and feel grateful for his support, guidance and generosity.

How do you see academia and activism working together to advance the protection and rights of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans communities in Canada?

First off, I would say that everyone at the university—students, faculty and staff—are all members of communities, inside and outside the university, both in the geographic sense and more generally in the way we belong to and participate in various communities. I see many of the students in our program doing work in community organizations, sometimes making contact through our program. For example, they might meet other folks here or visiting speakers and community members at events and talks we sponsor at the university and with organizations we partner with in the community. Those connections might develop from doing research at the ArQuives or through placements they take up as part of our service learning course, “Engaging Our Communities.” Most importantly, I think programs such as ours can give students the language, tools and (safe) spaces to do some of that work, particularly around equity and diversity, as well as the confidence and bravery they get from working with, inspiring, and challenging one another. Sometimes I hear from former students that they miss the kind of community, acceptance, and understanding they experienced at university, which may not necessarily exist in their own workplaces or communities. Others find and create spaces in which they are supported and feel a sense of belonging in ways they didn’t have a chance to experience here, and I think as educators we always need to be mindful of that.

How do you hope David’s inclusion in the National Portrait Collection will inspire the LGBTQ2+ communities?

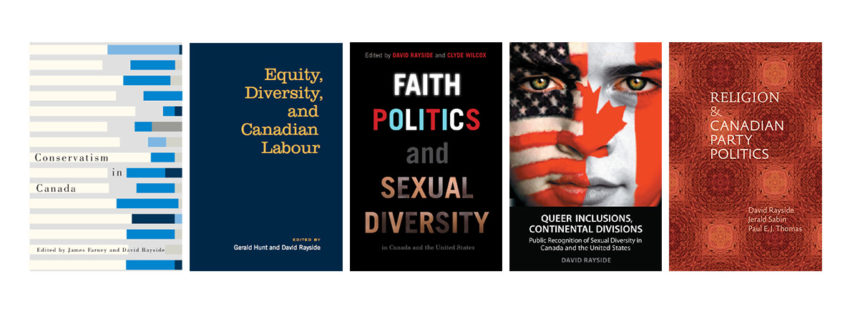

In the nearly 40 years he spent at University of Toronto, David has inspired students and colleagues alike through his teaching and his internationally recognized scholarship. His work provides insight into and challenges orthodoxy around issues of sexual diversity and LGBTQ2+ activism in Canadian politics, for example, the response to sexual diversity in faith-based communities, and the importance—and indeed, necessity—of understanding the place of religion in politics in this country, and elsewhere. I think his portrait, done by his niece Louisa Rayside, a talented photographer, will have meaning for all those who know David, especially because so much of the change he has helped inspire and make happen has come about through personal connections, reaching out to and collaborating with others both on campus and off. I remember when radio call-in shows about LGBTQ2+ issues were a big thing, and no matter where the show was taking place, including in some very right-wing and hostile forums, David would agree to be the expert guest. His ability to field questions, offer responses and challenge callers and other guests, clearly and calmly, and explain matters of diversity, equity and inclusion in ways that I think really connected with some folks who might have been encountering the topic, or really hearing it, for the first time. David is very adept and nimble when it comes to dealing with the media; however, it’s all of the things he’s done behind the scenes that I think have made lasting change and given a lot of folks, especially students, opportunities to learn and grow and step into the spotlight and take on that kind of work themselves.