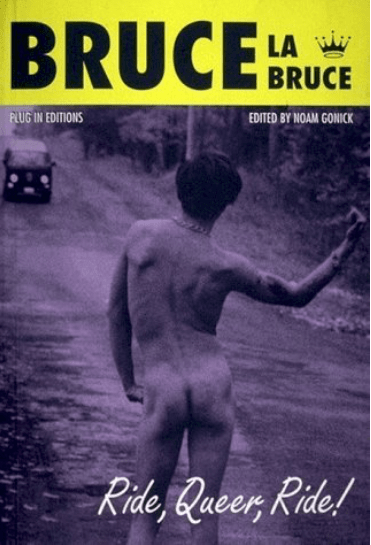

Ride, Queer, Ride! by Bruce LaBruce

When you open Ride, Queer, Ride! you are immediately met with several pages of black and white photography. You see photos of two men in a bathtub jerking each other off, a person putting a cigarette out on their tongue, some podophilia, a blow job, some bare asses, and more. Some are identifiable as stills from Bruce LaBruce’s films, and to begin the book like this is to acknowledge the theme of provocation that runs throughout LaBruce’s body of work. The book—a collage encompassing an interview, a journal chronicling the shooting of La Bruce’s Hustler White, film scripts for both No Skin Off my Ass and Super 81/2, essays, and more—appears designed in such a way as to mirror LaBruce’s zines, and is intended for an audience already familiar with the iconic artist’s work.

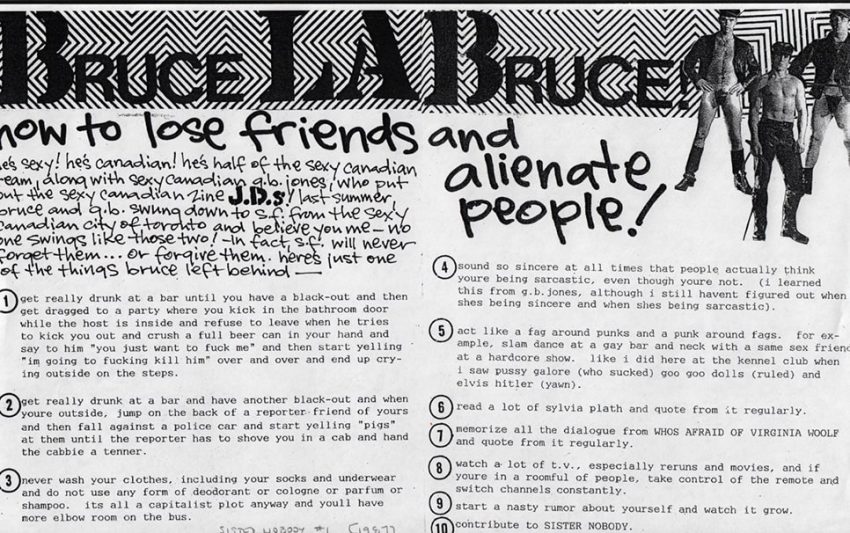

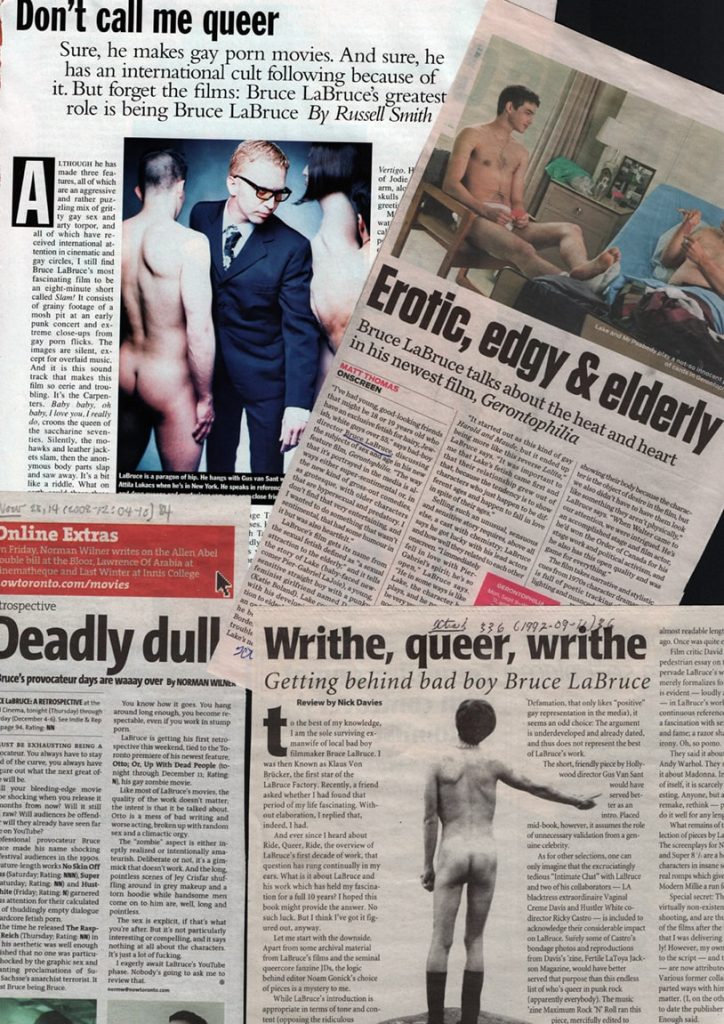

Who is Bruce LaBruce, and why is Ride, Queer, Ride! important? LaBruce has been an important figure in the Toronto queer community since the 1980s. He founded the queercore movement with a handful of friends—a movement that saw a massive output of zines, music, and films, and which bled to other cities throughout North America. He’s made over 20 films, both short and feature length, written two books, wrote regularly for Eye and Exclaim!, and wrote articles for countless other publications. He has pissed off and scandalized thousands and fascinated more. “Cameron Baily [sic] sardonically dubbed him Tonya Harding to director John Grayson’s Nancy Kerrigan,” says Noam Gonick, editor of the collection. Gonick further notes that LaBruce “explores the darker areas of the homosexual experience,” and, while Ride, Queer, Ride! lays out snippets of this exploration, the reader—particularly the uninitiated reader—will feel urged to learn more and dig into LaBruce’s vast backlog.

After Gonick’s introduction and a forward by LaBruce, Ride, Queer, Ride! jumps into a 1992 interview conducted between LaBruce, Vaginal Creme Davis, and Rick Castro, which essentially serves as a gossip session among the three. Following that, LaBruce’s production journal of Hustler White will entertain those who have seen the film. His published scripts—one of which he notes was formally written after the film had been released—are interesting to isolate from the visuals that normally accompany them. What is compelling about visiting his films as they are presented here is that there is something so very timeless about them, or at least the making of them. This timelessness is seen through the simple notion of young punks fed up with the system and deciding to create art on their own terms. Of just grabbing a camera, rounding up a few people, foregoing permits that you can’t afford, and just making the film. Considering the budget he made his films on, the sexual transgressions and ‘boundaries’ he was willing to acknowledge and clamber over in his content, and the wide audience he managed to reach while doing this, his work becomes all the more impressive.

LaBruce has been known to pass time with Gus Van Sant (who wrote an essay in this book) and Harmony Korine. The book contains a letter from Kurt Cobain in support of LaBruce’s work and ethos. The LaBruce fan will have fun pouring through Ride, Queer, Ride! as he namedrops—playfully, in a bragging sort of way, or matter-of-factly. This look at celebrity and fame, and how they intersect with the idea of authenticity, is discussed by David McIntosh in an essay in the book. “LaBruce has inserted his factitious history into this entropic system of industrialized celebrity, offering himself as the new raw material for exploitation in his own cottage industry version of the manufacture of stardom,” McIntosh writes, and “The greater the confusion and blurring of boundaries between self and system, reality and movies, the greater the need for signs of authenticity.” As a novice to LaBruce’s oeuvre, I found myself constantly questioning the level of authenticity of LaBruce—how much of his performance is staged? How much is real? How much does it matter? McIntosh argues that through putting himself at the centre of his own pornographic material, LaBruce is exposing himself on numerous levels, because “the eroticized meat self is the most authentic.”

This book is an enjoyable ride for someone who wants a behind-the-scenes look at the figure known as Bruce LaBruce. It’s a great way to fill in one’s knowledge on queercore history, queer punk aesthetics, and queer filmmaking. However, I would encourage the reader to visit LaBruce’s films and writing first. We have plenty of material at the ArQuives to prime you, including the films Skin Gang, Like This, Fifth Column, Otto: or Up with Dead People, and Queercore: A Punk-u-mentary, which was made by Scott Treleaven as the movement began to spread. We have LaBruce’s book The Reluctant Pornographer as well as issues of both his zine J.D.’s and other homocore/queercore zines including Homocore Rules, Anarcho-homocore Nite Club, Homocore, and Homocore Toronto. We have albums by the bands Pansy Division, Limp Wrists, The Fakes, and Kids on TV, groups from both Canada and the United States which identified as queercore/ homocore. And, if you are especially interested in the queercore movement, the film Queercore: How to Punk a Revolution is well worth a screening. Bruce LaBruce, who is worth following on Instagram, is currently at work on a new film.

Interview of Bruce La Bruce – TIFF Bell Lightbox Queer Outlaw – Retrospective