By Jeff Baillargeon

On August 28th, 1971, approximately one hundred individuals from Toronto Gay Action, the Montreal Front de Libération Homosexuel, the Homophile Association at the University of Toronto, and the Gays of Ottawa gathered on Parliament Hill to protest the ongoing discrimination of homosexuals in Canada. A similar demonstration was held on the same day in Vancouver for those who could not travel to Ottawa.

This, on the two-year anniversary of the (partial) decriminalization of homosexuality in 1969, was a reminder of the limitations of this amendment to the Criminal Code. As Charlie Hill, an organiser and speaker at the event, explained in a recent interview, “[a] lot of people, either gay or non-gay, thought there were no legal issues for gays. That was nonsense. There were still a lot of laws discriminating against gays. We did it in Ottawa because it was directed where federal laws were made.”

Although gloomy and rainy weather, and a relatively small crowd did not signal at the time a historic moment to the organisers, the We Demand protest is now regarded as the first gay liberation march in Canada. As Tom Warner argues, author of Never Going Back: A History of Queer Activism in Canada, “We Demand was a list of demands put together by a coalition of groups [that] formed the advocacy agenda for the next couple of decades.”

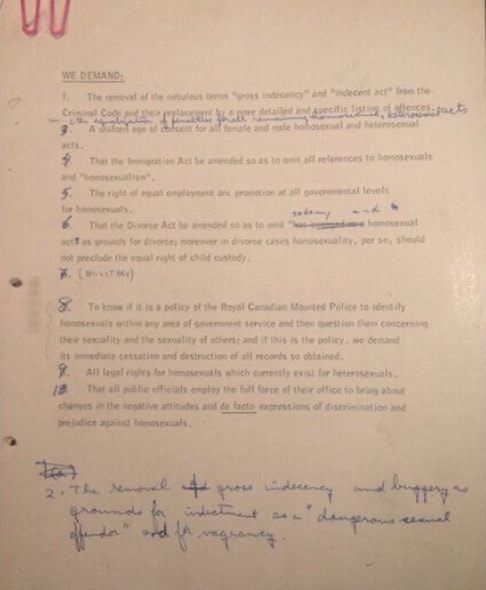

We Demand is a 13-page document including 10 demands for public policy changes to end all remaining forms of state sanctioned discrimination against homosexuals in Canada written by several queer individuals from the aforementioned organisations. As the letter states, “[i]n our daily lives we are still confronted with discrimination, police harassment, exploitation, and pressures to conform which deny our sexuality. That prejudice against homosexual people pervades society is, in no small way, attributable to practices of the Federal government.” A critique of the 1969 amendment, it addressed how the limitation to male adults above the age of 21 engaging in anal sex in the privacy of their own home—many of whom, we must add, did not enjoy this privilege of privacy—did not address the myriad ways in which homosexual men and women continued to face both implicit and violent forms of discrimination in our society.

https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/ron-levy/canadian-lgbtq-rights_b_8265052.html)

The ten demands called for the removal of derogatory signifiers to homosexual sexual acts in the Criminal Code such as “gross indecency” and “buggery,” as well as the removal of homosexuality as a ground for identification as a sex offender. It also called for the establishment of a universal age of consent regardless of sexual orientation. Furthermore, the letter called for the end of the ban to homosexuals from immigration into Canada, and to the removal of homosexuality as a legal ground for divorce or removal from child custody. In doing so, the letter demanded that homosexuality be removed from the same category as “physical or mental cruelty, bestiality, and rape” in legal statutes. The letter also demanded that homosexuals be protected in all levels of public service, and thus for an end to the purge of homosexuals by the RCMP (see The Fruit Machine Documentary). Lastly, the letter demanded that protection from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation be added to Canadian Human Rights laws.

As the letter argued, these state sanctioned forms of discrimination signalled and enabled the denial of full citizenship to homosexual men and women in Canada. As it concluded, “[i]n a democratic society, if one minority is denied freedom, all citizens are oppressed.”

Despite being recognised as a milestone in Canadian queer history today (albeit limited to cis-queer individuals), at the time it received little support both inside and outside of the queer community. This would remain a problem in the decades to come, highlighting a tension between those who believe acceptance of difference is won by explicit struggle, such as was waged by the members of We Demand, and those who believe it is won by silent assimilation. It was not uncommon at this time for gay activists, groups, and publications to receive the following backlash as did The Body Politic in 1978:

“If you think that by publishing articles that infuriate the public and create a backlash against us you are doing us a service, you had better think again. […] It may surprise you to know that most of us prefer to keep a low profile about our sexual preferences, and don’t need noisy idiots like you to harm us. Why don’t you just shut up?”

But given the level of state-sanctioned discrimination the We Demand list highlighted, it is not hard to understand why certain individuals have felt this way about queer activist politics at times. This only further signals the need for community outreach and support. Today, it is a very different scene where Pride draws thousands of individuals into the streets, but there still remains many individuals and groups for whom visibility is a privilege they cannot access without a degree of fear of physical, economic and social violence. We must continue marching for them, and centering their voices in our activism.