Sophie takes a dive into the raiding of The Body Politic, the community response, and privacy and censorship.

Raiding the Office

On December 30, 1977 at 5 pm, four Metropolitan Toronto Police officers and one Ontario Provincial Police officer raided the office of Pink Triangle Press, the publisher of The Body Politic magazine1. The officers were armed with a search warrant that “authorized [them] to search for ‘corporate records, invoices and documents pertaining to business operations’ which would afford evidence relevant to charges which might be laid under Section 164 of the Criminal Code of Canada”2. Section 164 refers to “use of the mails for the purpose of transmitting or delivering anything that is obscene, indecent, immoral or scurrilous”3. The charges were specifically related to the article written by Gerald Hannon, ‘Men Loving Boys Loving Men’, published in the December/January issue of The Body Politic4. You can read the article for yourself here.

The officers combed through the office for three and a half hours and left with 12 cartons of material5. The material taken included subscriber lists, unpublished manuscripts, classified advertising records, letters to the editor, and financial records6. They also took “all copies of The Joy of Gay Sex, The Joy of Lesbian Sex and Loving Man that were on the premises”, even though these books had been approved by customs and were being sold elsewhere in the city7. Ed Jackson, Body Politic collective member and secretary of Pink Triangle Press said, “[i]t seemed like everything we needed to continue publication walked out the door…”8. The timing of the raid was particularly devious. The raid occurred on the Friday before the New Year’s long weekend. This “meant they could walk out of [there] with everything and spend the next four days going over it. [The Body Politic] couldn’t even begin legal manoeuvres to quash the warrant until the world got back to normal after New Year’s and that was the following Tuesday”9.

Media attention is a large reason why this raid occurred. The Body Politic explained that an influx of concerned letters from readers did not come immediately after the controversial article was published on November 21. Instead, letters started coming in after the article received media attention on December 2210. Toronto Sun’s reporter on the Ontario Legislature, Claire Hoy launched an attack against The Body Politic, drawing attention to the article and claiming it was “promoting child abuse”11. The Toronto Sun’s homophobic commentary continued throughout the trial. In an editorial on January 5, 1978, the Toronto Sun called The Body Politic “[a] crummy, dirty publication without a redeeming feature”12. Writing for The Body Politic, Chris Bearchell warned that the media’s distorted coverage of queer issues was intentional. She wrote “note this omen: the Queen’s Park parliamentary Press Gallery recently elected its new president. His name? Claire Hoy. If 1977 was the media year of the queer, 1978 looks suspiciously like the media year of the queer-basher”13.

A Lengthy Court Battle

Shortly after the raid, the magazine’s defence lawyer, Clayton Ruby asserted that “the search warrant used during the raid was illegal under Canadian law14. His reasons were as follows: “it did not properly specify the offence for which it was issued, it did not list with sufficient precision the materials which could be searched for and seized, and the justice of the peace issuing the warrant was not acting judicially as is required by law, because s/he did not have reasonable grounds to believe that the December/January issue of TBP was immoral”15. Ruby quickly “initiated an action in the Supreme Court of Ontario to quash the warrant and demand the return of everything taken in the raid”16. This was unsuccessful17. Almost two years after the first raid and almost one year since their acquittal, “most of [the seized] material, including lists of subscribers, [had] still not been returned”18. The Body Politic went to court to demand that the materials be returned and “to seek a court order forcing the police to return this material”19. Ruby argued that these materials should not have even been seized in the first place. “According to Ruby, all the police needed to press charges was a copy of the paper and proof that [The Body Politic] distributed it. Proof of distribution could have been obtained from the post office”20. Other than one copy of the December/January issue, these materials were not used as evidence in the trial, so there was no reason for the police to retain them21.

On January 5, 1978, charges were laid against Pink Triangle Press and against its president Ken Popert, secretary Edward Jackson, and treasurer Gerald Hannon22. Almost one year later, on January 2, 1979, the trial began before Provincial Court Judge Sydney Harris23. Communication and Censorship specialist, Thelma McCormick, “noted in her testimony for the defense that the Body Politic article was no more obscene than many stories which are published in Toronto’s daily papers”24. On February 14, Provincial Court Judge Sydney Harris ruled that “Parliament has failed to define immorality clearly enough for the courts to judge what is moral or immoral”, which Clayton Ruby called a landmark decision25. The Body Politic and its executives were found not guilty26.

On March 6, the Crown appealed the verdict, with Attorney General McMurtry trying to overturn the decision27. McMurtry denied that this decision was political, which was hard to believe since there were votes to be gained from attacking the queer community; voters who were angry about the acquittal even marched outside of Queen’s Park28. Despite the magazine’s appeals to the Ontario Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court of Canada, The Body Politic’s acquittal was overturned and a date for a new trial was set29.

This retrial was seen as unjust by The Body Politic, who claimed it contravened the principle of Double Jeopardy. The Double Jeopardy rule is “the traditional right of citizens not to be tried more than once on the same set of charges and, especially, the right not to be tried again after being found innocent […] but there’s no law to stop [this] from happening in Canada whenever an attorney general feels the itch”30. Fortunately, on May 31, The Body Politic was acquitted once again31. This court battle spanned over three years and cost the magazine and taxpayers tens of thousands of dollars.

Raided Again

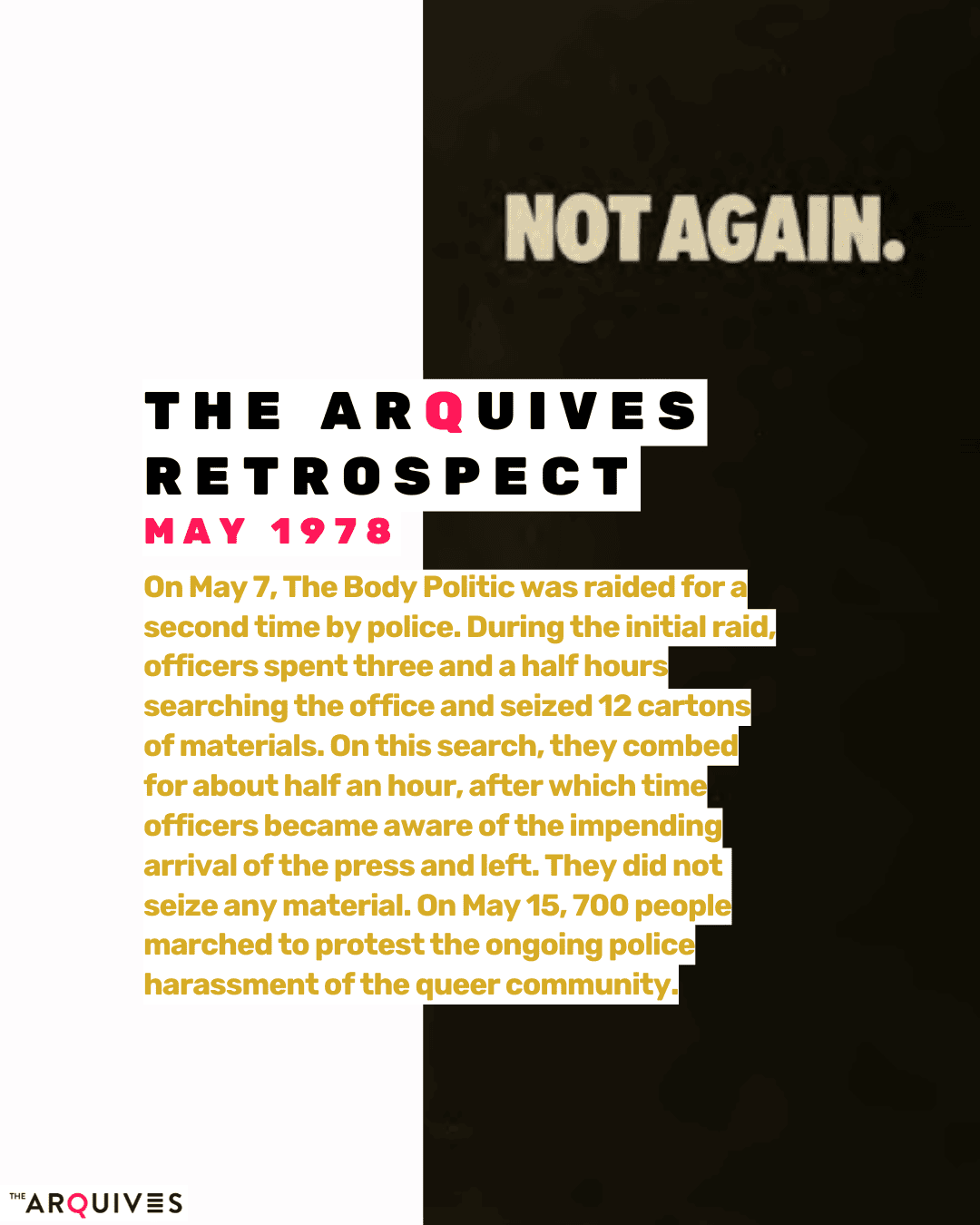

On May 7, 1982, “two officers from the Morality Bureau of the Metropolitan Toronto Police, carrying a familiar looking catch-all search warrant, entered the offices of The Body Politic”32. Unlike the first raid, this one was not prompted by any public complaint about the content33. The officers said they were looking for evidence to support a charge of publishing obscene written matter34. Specifically, they were seeking to charge them for publishing the article, “Lust with a Very Proper Stranger,” which discussed the etiquette of fist-fucking35. This article’s author used the pseudonym Angus Mackenzie36. The officers raiding the office were intent on discovering the identity of the author37. “The search of [The Body Politic] lasted for about half an hour, after which time [the officers] became aware of the impending arrival of the press and left”38. In the end, the officers did not seize any material39.

On May 7, charges for “publishing obscene written matter” were laid against “all nine members of the TBP editorial collective and Pink Triangle Press”40. Edward Arthur Jackson, Gerald Hannon, Timothy McCaskell, John Allec, Christine Bearchell, Richard Bebout, Stephen MacDonald, Roger Spalding, and Ken Popert were all charged41. This “meant that an entire editorial board was suddenly swept up in emergency meetings, consultations with lawyers, surrendering for arrest, fingerprinting, photographing, court appearances, [and] press conferences”42; undoubtedly, this made it difficult for the publisher to continue its work. “If convicted under Section 159(1) of the Criminal Code, collective members each [faced] a maximum penalty of $1,000 fine and six months imprisonment. Pink Triangle Press could [have received] an unlimited fine”43.

This obscenity charge was seen as highly unfair since many heterosexual publications such as Penthouse discussed the same subject and received no punishment44. The Body Politic asserted that “[v]irtually every milk store in the city has sold far more explicit descriptions of fist-fucking than the rather circumspect account provided in [The Body Politic]”45. On May 15th, 700 people marched to protest police harassment of the queer community, chanting, “[w]e are all Angus MacKenzie”46.

The queer community saw the timing of the charges as suspicious. These charges were laid when the magazine’s retrial regarding their 1978 ‘Men Loving Boys Loving Men’ article was only three weeks away47. “The timing of the charges [led] The Fund to conclude that the Crown’s aim [was] not to obtain a conviction, but to keep The Body Politic before the courts, draining it of the financial and human resources needed to keep fighting on the legal front”48. The trial began on November 1, 198249. The Body Politic were confident that they would win once again and they were correct50. The judge ruled that the magazine was not obscene and all nine collective members were acquitted51. While the Crown was unsuccessful in convicting the magazine, it did manage to tie them up in a four-year-long, costly legal battle.

Community Response

After the first raid, many community members blamed The Body Politic for publishing an article about pedophilia. Some community members saw aligning with queer pedophiles as putting a target on the back of the entire community. One reader wrote, “I’m a homosexual and you’re a damn fool. If you think that by publishing articles that infuriate the public and create a backlash against us you are doing us a service, you had better think again. That stupid article about teachers and Big Brothers loving boys (and glorifying them for it) has set us back several years”52. Another reader wrote, “[t]he legitimization of same-sex love among adults is a far more important and accessible aim than the legitimization of adult-child eroticism. If the two are linked, the latter can only hinder the former. Let’s not spread our efforts too thinly”53. These readers were particularly concerned that this article was published at a dangerous time: Anita Bryant was about to come to Toronto with her bigoted “Protect the Children” campaign and queer rights were soon being debated before The Ontario Human Rights Commission54. These readers had little sympathy for The Body Politic’s predicament.

On the other hand, some readers really appreciated the article. One reader wrote, “I appreciate a great deal your finally publishing the article ‘Men Loving Boys Loving Men’. The debate within the Collective mirrors the debate within the gay movement itself on the approach toward youth sexuality”55. Another reader felt represented by the article: “Your recent article, ‘Men Loving Boys Loving Men’, made me proud to be what I am. Yes. l am a pedophile (odious term): l love boys. I love men, too, and have been known to love women. Having had entirely satisfactory, loving, sexual relationships with women, men, and boys. I find that I prefer boys — boys generally 12 to 14 years of age, some younger, some older”56. I must admit I have a visceral negative reaction to hearing someone proclaim their sexual attraction to 12-year-old boys. My reaction is unsurprising though because today the community consensus is that pedophiles should not be included or tolerated in the LGBTQ+ community. It is important to approach historical material with an awareness of the context in which the community was operating at the time.

The Body Politic defended their choice to publish this article. They explained that “[c]hild/adult relationships are misunderstood, and that misunderstanding is used against all gay people. Those people who wish we wouldn’t talk about it at all forget that the people who oppose us won’t stop talking about it. And when they talk about it, they call it child molestation. As the battle for gay rights heats up, the ‘molestation tactic’ is going to be more and more the weapon we’ll have to face. And we can’t face what we don’t understand”57. I do not really believe that child/adult relationships were being misunderstood, but I do believe that the article is mostly irrelevant; the real issue is the targeting of a queer publication. If you, like myself are disgusted by the article, you must at least recognize the steps that could have been taken by authorities to prevent the press from publishing similar articles in the future, none of which needed to involve a raid or a criminal charge.

As The Body Politic argued, “The real question is why [the article] provoked such a violent reaction. We think it’s a desire to impede the real advances being made by gay people. The Ontario Human Rights Commission wants to see “sexual orientation” in the Human Rights Code”58. I tend to agree with the groups who held a more nuanced view, such as one who wrote, “[a]s concerned as we are though about the article, we are even more concerned about the police raid on your offices and the ensuing charges. The raid was clearly a violation of the tradition of freedom of the press all Canadians have a right to enjoy”59. Similarly, The Atlantic Provinces Political Lesbiane warned about pitting respectable gays against indecent gays:

No matter how we feel about ‘Men Loving Boys Loving Men’, or further discussions of pedophiles, we must not let this divide us. We must respect the fact that freedom of the press (and freedom of speech and freedom of thought) allows discussion of this and all other thoughts and ideas that float through our brains, even if others don’t respect this freedom. Let us talk and listen, and talk. Even if we disagree among ourselves, let us continue the dialogue. And stand united60.

While the debate about child/adult relationships made queer people hesitant to defend The Body Politic, members of the public did eventually come to the magazine’s aid61. In their February 1978 issue62, The Body Politic thanked their supporters: “More people than can be named here deserve our thanks — those who provided moral support and encouragement, those who volunteered to help, those who offered their services for the long-term defence efforts. And those who gave money”. They also wrote, “[s]upport from the gay community and from concerned organizations, both gay and straight, is probably the main reason why The Body Politic has been able to continue publishing”63. The community’s response to this raid shows the power of banding together to defend queer rights. Much to the chagrin of the right wing, even Toronto Mayor John Sewell voiced his support for the queer community in the time leading up to the first trial64.

Financial donations enabled The Body Politic to stay afloat during the four years of court costs. In just one month, supporters raised over $10,000 for The Body Politic Free the Press Fund65. By December 1981, the Fund had raised $67,80066. They raised this money by calling for donations in The Body Politic and by holding fundraising events. On December 30, 1978, they hosted a fundraising party called “Raid!” “in celebration of the first anniversary of the police sweep of the magazine’s office”67.

Various demonstrations were held in Toronto protesting the targeting of The Body Politic. On March 23, The Body Politic Free the Press Fund organized a 60-person march outside of Attorney General Roy McMurtry’s office68. Following the second raid, 700 people marched to protest the targeted attack69. These demonstrations were key for garnering public support, pressuring the authorities and drawing attention to the injustice.

The Body Politic Free the Press Fund received support from publications and organizations in London, San Francisco, Australia, and New York City70. Gay Alliance Towards Equality (GATE) Vancouver actually held the first demonstration protesting the raid71. In San Francisco, the iconic Harvey Milk called for a tourist boycott of English Canada to protest this censorship72. The widespread support of The Body Politic was impressive, especially since this was before the internet existed to connect queer people across the world. This shows the importance of fostering a global queer movement.

Privacy and Censorship

In the first raid, the police “took subscription lists dating years into the past…It was an obvious attempt to terrorize the readers of a newspaper by seizing its subscription list”73. This attempt was somewhat successful. Only a quarter of The Body Politic’s copies are purchased via subscription. When asked why they didn’t subscribe, a fifth of respondents cited fear as their reason:

Nearly 50 of those who answered said they didn’t want to receive a gay magazine in the mail, or that they were worried about everyone from the nosey local postmaster to their roommates or parents seeing it. Twenty-eight said specifically that they were afraid to have their name on TBP’s mailing list — a fear increasingly reported since the 1977 raid on our office, during which subscription lists were seized74.

This raid intimidated readers from doing something that is already a privacy risk. Members of the queer community had to decide between accessing a valuable queer community resource and protecting their privacy. Subscribing to a queer publication was already a risk at the time since someone could be outed by the delivery. After the raid, readers were also worried about being targeted by a police force that had already proven itself to be anti-queer. Threats to privacy can have a very real chilling effect on queer cultural practices. The same chilling effect can be seen on social media sites that are designed in a way that risks outing users to their friends and family; queer users will simply decide not to engage with queer community on these platforms.

The warrant used and the raid set dangerous precedents for freedom of the press in general. In a Book & Periodical Development Council Newsletter, Sheila Kieran wrote, “[t]hose of us concerned with the right of comment in a free society must be apprehensive when, as in the case of the Body Politic magazine, police clearly overstep necessity in confiscating material in an obscenity case”75. A Criminal Lawyers Association Newsletter said, “[w]e have criticized the obscenity laws before for their uncertainty, and the powers given to law enforcement officials to impose prior censorship – but never before have we had such a blatant example of their futility”76. The vagueness of obscenity laws allowed the police and the Crown to suppress a queer publication. These same vague guidelines and unwritten rules can be found on social media sites today, which ban and suppress queer content without any recourse. We must be wary of relying on any medium that is governed by those who are indifferent or even antagonistic to queer people.

These raids were specifically concerning because the Pink Triangle Press offices also held the Canadian Gay Archives. Files from the archives section were seized in the raid. The Body Politic found this alarming, and explained that “The Archives is a member in good standing of TAAG — Toronto Area Archivists Group, and James Fraser, the gay archives co-ordinator, reports that several TAAG members are very concerned that police can enter an archives and look through material unrelated to charges they are investigating”77. In The Archives Bulletin, James Fraser also asked, “[c]an archives continue to assure donors with any certainty that their records will remain confidential so long as we know that police do act in such a way?”78. These actions could be seen as a threat to all archives, and this shows us that unfettered police power prevents us from safely preserving the histories of marginalized groups. It is incredibly important to clarify laws so that marginalized people can be protected, and not targeted, when things take a bad turn.

References

- The Body Politic. (1978, February). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic40toro; The Body Politic. (1979, November). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic58toro

- The Body Politic. (1978, February). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic40toro

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The Body Politic. (1978, February). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic40toro; The Body Politic. (1979, November). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic58toro

- Ibid.

- The Body Politic. (1978, February). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic40toro

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The Body Politic. (1978, February). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic40toro; The Body Politic. (1982, May). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic83toro

- The Body Politic. (1978, March). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic41toro

- Ibid.

- The Body Politic. (1978, February). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic40toro

- The Body Politic. (1978, March). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic41toro

- The Body Politic. (1978, February). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic40toro

- The Body Politic. (1982, May). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic83toro

- The Body Politic. (1979, November). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic58toro

- Ibid.

- The Body Politic. (1978, February). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic40toro

- The Body Politic. (1982, May). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic83toro

- The Body Politic. (1978, February). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic40toro

- The Body Politic. (1982, May). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic83toro

- Media (non-gay)coverage of trial and raid. (1979-1980). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions20865

- Body Politic- Raid and Trial. (1978-1980). GayAlliance Toward Equality (Vancouver) fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions23080

- The Body Politic. (1982, May). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic83toro

- Ibid.

- Media (non-gay)coverage of trial and raid. (1979-1980). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions20865

- The Body Politic. (1982, May). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic83toro

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The Body Politic. (1982, June). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic84toro

- The Body Politic Second Raid/Charges Published Materials, Media Coverage. (1982, May 7). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions21627

- The Body Politic. (1982, June). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic84toro

- Ibid.

- The Body Politic. (1982, July/August). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic85toro

- The Body Politic Second Raid/Charges Published Materials, Media Coverage. (1982, May 7). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions21627

- The Body Politic. (1982, June). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic84toro

- The Body Politic. (1982, July/August). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic85toro

- The Body Politic. (1982, June). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic84toro; The Body Politic. (1982, July/August). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic85toro

- The Body Politic Second Raid/Charges Published Materials, Media Coverage. (1982, May 7). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions21627

- The Body Politic. (1982, June). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic84toro

- The Body Politic. (1982, July/August). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic85toro

- The Body Politic. (1982, June). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic84toro

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The Body Politic. (1982, July/August). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic85toro

- Ibid.

- The Body Politic. (1982, June). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic84toro; The Body Politic Second Raid/Charges Published Materials, Media Coverage. (1982, May 7). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions21627

- The Body Politic Second Raid/Charges Published Materials, Media Coverage. (1982, May 7). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions21627

- The Body Politic. (1978, February). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic40toro

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The Body Politic. (1978, March). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic41toro

- The Body Politic. (1978, February). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic40toro

- Ibid.

- The Body Politic. (1978, March). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic41toro

- Ibid.

- The Body Politic. (1979, November). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic58toro

- The Body Politic. (1978, February). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic40toro

- Ibid.

- Media (non-gay)coverage of trial and raid. (1979-1980). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions20865

- The Body Politic. (1982, May). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic83toro

- Ibid.

- The Body Politic. (1979, February). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic50toro

- The Body Politic. (1982, May). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic83toro; Raid on The Body Politic, Coverage by media. The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions21576

- The Body Politic. (1982, June). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic84toro

- Raid on The Body Politic, Coverage by media. The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions21576

- The Body Politic. (1982, May). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic83toro

- Ibid.

- The Body Politic. (1978, February). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic40toro

- The Body Politic. (1981, November). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic78toro

- Raid on The Body Politic, Coverage by media. The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions21576

- Media (non-gay)coverage of trial and raid. (1979-1980). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions20865

- The Body Politic. (1978, February). The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/ia_bodypolitic40toro

- Raid on The Body Politic, Coverage by media. The Body Politic fonds. The ArQuives. https://collections.arquives.ca/link/descriptions21576

Author Bio: Sophie Argyle is a Master’s student in York University’s Communication and Culture program. In her research, she examines the possibilities and limitations offered to LGBTQ+ people by digital media. She is currently writing her thesis about queer people who discovered a facet of their LGBTQ+ identity on TikTok. As an intern at the ArQuives, Sophie is excited to help out the communications team and research historical events that involved the collection of queer people’s personal data.