Showing our Pride from Toronto, Halifax, Montreal and Vancouver.

Written by: Allison Ridgway

Toronto On 1 August 1971, Toronto’s gay and lesbian community held its first Pride celebration: a Gay Day picnic. Around 300 people gathered at Hanlan’s point, decorating the Toronto Islands beach with flags, banners and balloons to declare their Pride. Organized by Toronto Gay Action, the Community Homophile Association of Toronto and the University of Toronto Homophile Association, that afternoon was more than just a party: it was one of the city’s first – and largest – displays of gay and lesbian solidarity, and the first step in making Toronto Pride the cultural landmark it is today.  The following year, Pride Day grew into Pride Week: seven days filled with film screenings, art festivals, panels and dances. The week culminated in Toronto’s first Pride march, held 19 August 1972. This first march looked much different than the one held last weekend. There were no mass crowds lining the streets and waving rainbow flags to cheer on the marchers like we see today. Despite efforts by the organizers, then-Mayor David Crombie and city council refused to officially declare Gay Pride Week, though he did send well wishes to the revelers.

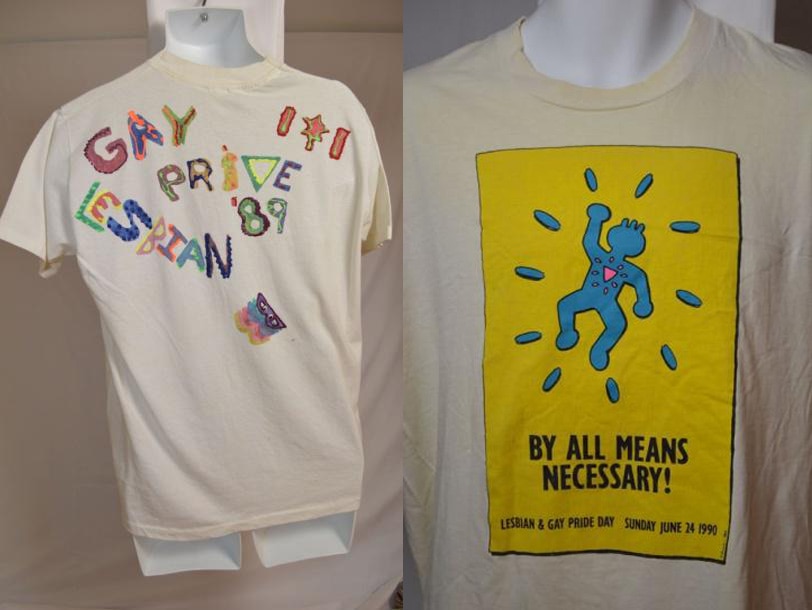

The following year, Pride Day grew into Pride Week: seven days filled with film screenings, art festivals, panels and dances. The week culminated in Toronto’s first Pride march, held 19 August 1972. This first march looked much different than the one held last weekend. There were no mass crowds lining the streets and waving rainbow flags to cheer on the marchers like we see today. Despite efforts by the organizers, then-Mayor David Crombie and city council refused to officially declare Gay Pride Week, though he did send well wishes to the revelers.  Pride Weeks continued throughout the 1980s, growing from under 2,000 attendants in 1981 to over 25,000 people by the beginning of the 1990s. The 1989 Pride festival’s theme was “Vision 20/20: Setting Our Sights” to recognize the 20th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots in New York. In 1991, then-Mayor June Rowlands and City Council proclaimed Pride for the first time, and in 1995, Mayor Barbara Hall became the first head of council to march in the parade.

Pride Weeks continued throughout the 1980s, growing from under 2,000 attendants in 1981 to over 25,000 people by the beginning of the 1990s. The 1989 Pride festival’s theme was “Vision 20/20: Setting Our Sights” to recognize the 20th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots in New York. In 1991, then-Mayor June Rowlands and City Council proclaimed Pride for the first time, and in 1995, Mayor Barbara Hall became the first head of council to march in the parade.  The first official Dyke March took place in 1996 and saw about 5,000 people turn out for the event. The first Trans March was held in 2009. That same year, Toronto Pride grew to an estimated 750,000 revelers, making it one of the largest LGBTTQ festivals in the world.

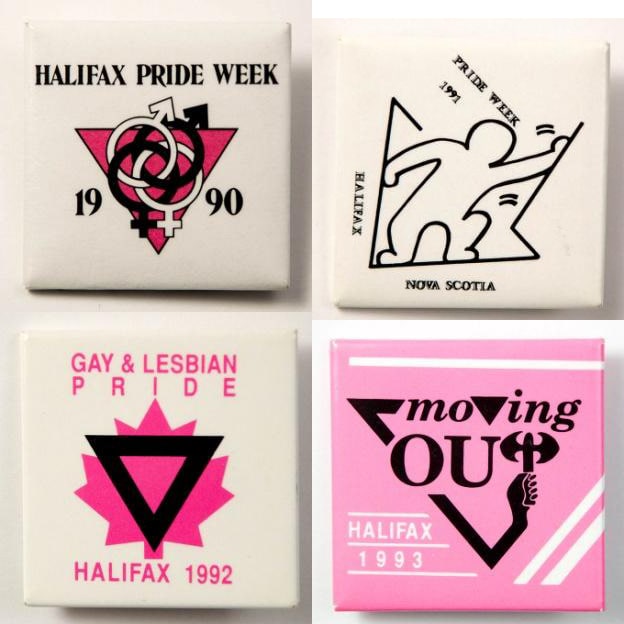

The first official Dyke March took place in 1996 and saw about 5,000 people turn out for the event. The first Trans March was held in 2009. That same year, Toronto Pride grew to an estimated 750,000 revelers, making it one of the largest LGBTTQ festivals in the world.  Forty-three years after that first Gay Day picnic at Hanlan’s attended by just 300 people, people from all over the world lined Yonge Street last year to cheer on over 12,000 marchers during last year’s WorldPride parade. It was the first time the WorldPride festival took place in a North American City. Halifax Halifax’s first Pride March in 1987 was much more of a protest than a celebration, and the city’s gay and lesbian community came together to rally against the lack of legal protection from discrimination and homophobic violence. About 75 people marched through Halifax’s North End that year. According to Halifax Pride, some marchers wore bags over their heads for fear that being seen marching in the Pride Parade would compromise their safety. Since then, the Halifax Pride Festival has become the largest LGBTQ+ event in Atlantic Canada and one of the largest Pride events in the country. Last year, approximately 2,500 people marched through the city’s downtown as at least 80,000 people cheered them on – a far cry from the city’s first parade, and a moment made possible through the courage of those who marched through Halifax’s streets in 1987 to declare their pride.

Forty-three years after that first Gay Day picnic at Hanlan’s attended by just 300 people, people from all over the world lined Yonge Street last year to cheer on over 12,000 marchers during last year’s WorldPride parade. It was the first time the WorldPride festival took place in a North American City. Halifax Halifax’s first Pride March in 1987 was much more of a protest than a celebration, and the city’s gay and lesbian community came together to rally against the lack of legal protection from discrimination and homophobic violence. About 75 people marched through Halifax’s North End that year. According to Halifax Pride, some marchers wore bags over their heads for fear that being seen marching in the Pride Parade would compromise their safety. Since then, the Halifax Pride Festival has become the largest LGBTQ+ event in Atlantic Canada and one of the largest Pride events in the country. Last year, approximately 2,500 people marched through the city’s downtown as at least 80,000 people cheered them on – a far cry from the city’s first parade, and a moment made possible through the courage of those who marched through Halifax’s streets in 1987 to declare their pride. Montreal From 1981 to 1986, various community groups in Montreal organized parades at the end of June under the names “Gai-lon-la”, “Marche Bleu Blanc Rose” and “Fête Nationale” (when the Pride date coincided with the anniversary of New York’s Stonewall riots). The city had experienced its own Stonewall just five years later on 15 July 1990, when a group of Montreal police officers violently arrested and humiliated at least 400 gay, lesbian and transgender people attending a party at the Sex Garage in Old Montréal. Images of the arrests were broadcast throughout international media, leading to mass protests that night and the night following. The city’s LGBT community mobilized, as activists and community organizers fought against the police violence, arrests and discrimination. It also sparked the creation of the Black and Blue festival in 1991. The proceeds from this party raise money for those arrested during the raids. The party has since grown into the world’s largest gay-benefit dance and pride festival. Now organized by Bad Boy Club Montréal, it continues to raise money for LGBTQ and AIDS organizations. While no Pride Parade was held in 1992, the following year saw the creation of Divers/Cité by Suzanne Girard and Puelo Dier, a Gay Pride and arts festival that celebrated local and international LGBT culture. The birth of the festival fueled a boom in LGBT tourism to Montréal, and in 1996 the festival introduced one of its most renowned events: Masacara: Le Nuit des Drags concert and drag show. The annual show drew audiences of up to 25,000 people until its end in 2013. Fiérte Montréal Pride took over the city’s annual parade from Divers/Cité in 2007, and has organized it ever since. The 35th anniversary of Montréal’s Pride celebrations in 2017 will also be the first inaugural Canada Pride Parade and Festival. The festival, which has been modeled after EuroPride and WorldPride, is expected to welcome one million people from across Canada and the world.

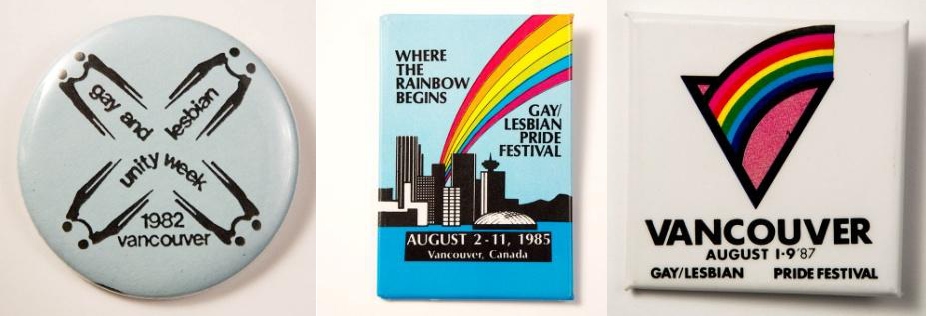

Montreal From 1981 to 1986, various community groups in Montreal organized parades at the end of June under the names “Gai-lon-la”, “Marche Bleu Blanc Rose” and “Fête Nationale” (when the Pride date coincided with the anniversary of New York’s Stonewall riots). The city had experienced its own Stonewall just five years later on 15 July 1990, when a group of Montreal police officers violently arrested and humiliated at least 400 gay, lesbian and transgender people attending a party at the Sex Garage in Old Montréal. Images of the arrests were broadcast throughout international media, leading to mass protests that night and the night following. The city’s LGBT community mobilized, as activists and community organizers fought against the police violence, arrests and discrimination. It also sparked the creation of the Black and Blue festival in 1991. The proceeds from this party raise money for those arrested during the raids. The party has since grown into the world’s largest gay-benefit dance and pride festival. Now organized by Bad Boy Club Montréal, it continues to raise money for LGBTQ and AIDS organizations. While no Pride Parade was held in 1992, the following year saw the creation of Divers/Cité by Suzanne Girard and Puelo Dier, a Gay Pride and arts festival that celebrated local and international LGBT culture. The birth of the festival fueled a boom in LGBT tourism to Montréal, and in 1996 the festival introduced one of its most renowned events: Masacara: Le Nuit des Drags concert and drag show. The annual show drew audiences of up to 25,000 people until its end in 2013. Fiérte Montréal Pride took over the city’s annual parade from Divers/Cité in 2007, and has organized it ever since. The 35th anniversary of Montréal’s Pride celebrations in 2017 will also be the first inaugural Canada Pride Parade and Festival. The festival, which has been modeled after EuroPride and WorldPride, is expected to welcome one million people from across Canada and the world.  Vancouver In the early 1970s, Pride celebrations in Vancouver included picnics held in Ceperley Park that marked the birth of the city’s Gay Pride Week (later called Gay Unity Week). The celebrations continued to grow throughout this decade, featuring art festivals, dances, picnics and rallies for gay and lesbian rights. In 1981, a Gay Unity Week parade beginning at Nelson Park attracted an estimated 1,500 attendants. The previous year, Vancouver’s city council had refused to officially declare Gay Unity Week, and conservative aldermen and clergymen railed against the parades as “immoral”. This changed in 1981, however, as newly-elected Mayor Mike Harcourt officially proclaimed Gay Unity Week after promising to do so during his election campaign. In 2013, Vancouver’s Pride parade was officially designated a civic event. Today, Vancouver’s Pride Parade is the largest parade in Western Canada.

Vancouver In the early 1970s, Pride celebrations in Vancouver included picnics held in Ceperley Park that marked the birth of the city’s Gay Pride Week (later called Gay Unity Week). The celebrations continued to grow throughout this decade, featuring art festivals, dances, picnics and rallies for gay and lesbian rights. In 1981, a Gay Unity Week parade beginning at Nelson Park attracted an estimated 1,500 attendants. The previous year, Vancouver’s city council had refused to officially declare Gay Unity Week, and conservative aldermen and clergymen railed against the parades as “immoral”. This changed in 1981, however, as newly-elected Mayor Mike Harcourt officially proclaimed Gay Unity Week after promising to do so during his election campaign. In 2013, Vancouver’s Pride parade was officially designated a civic event. Today, Vancouver’s Pride Parade is the largest parade in Western Canada.

About the Author: Allison Ridgway is a volunteer with The ArQuives Communications Committee.

About the Author: Allison Ridgway is a volunteer with The ArQuives Communications Committee.